DON’T LIVE ‘ERE, DON’T SURF ‘ERE

In Lorcan Finnegan’s The Surfer, the Australian coast is not a paradise—it is a psychological crucible. Sweltering, gleaming, indifferent. Here, the sun beats down like an interrogator’s lamp, and the sea gleams like a mirror held too long to one’s face. It is not just water and sand. It is memory. Madness. Masculinity rotted in the sun.

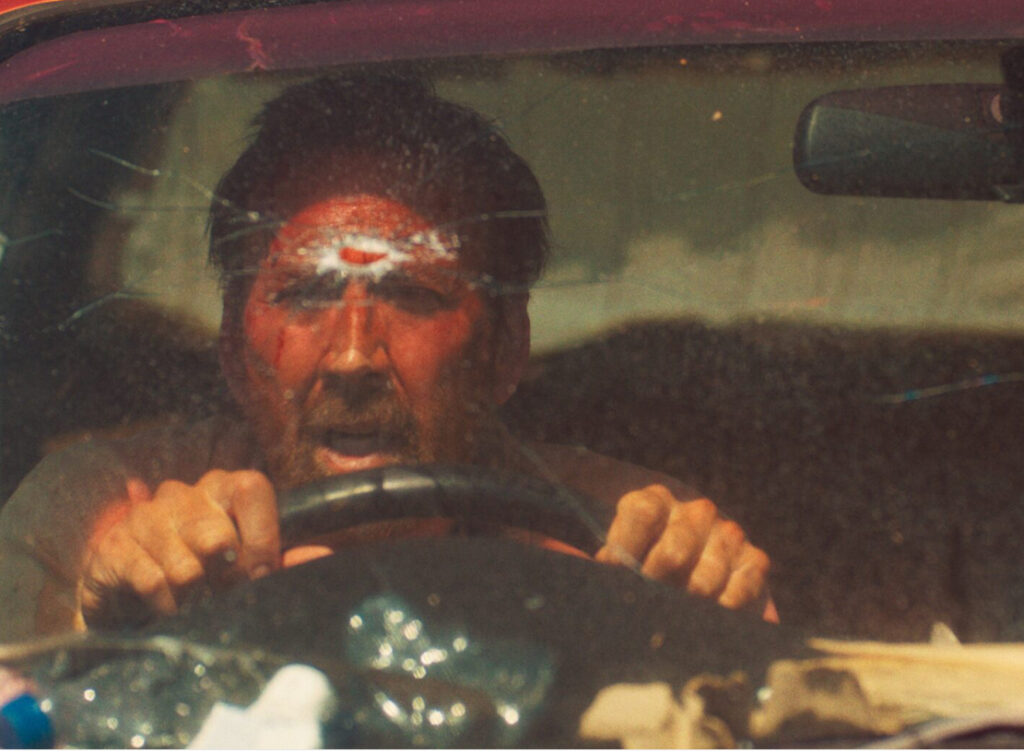

Into this crucible comes Nicolas Cage, a man without a name, referred to only as “The Surfer.” He’s a figure out of time—a local legend turned stranger in his own land. A father, a failure, a ghost who won’t leave the shore. Banished from his childhood surf spot by younger, rougher men—territorial, tribal, almost mythological in their dominance—he refuses to leave. And as the temperature rises, so does the tension. Not unlike Wake in Fright, Straw Dogs, or The Beach, The Surfer is a story of place as pressure, and of manhood as a thing cracked open under that pressure.

What begins as a spat between beachgoers escalates into a slow-burn psychodrama of sunstroke, sand, shame, and surrealism. This is Finnegan’s most stripped-back film to date, but also his most mythic—shot through with folklore texture and existential dread, like a parable told under duress. And in Cage, he’s found the perfect totem of collapse.

Lorcan Finnegan’s Cinema of Psychological Deterioration

Lorcan Finnegan is no stranger to films about space—both the psychic and physical kind. In Vivarium (2019), he turned suburban housing estates into a looping hell. In Without Name (2016), he unraveled identity through environmental horror. The Surfer, though vastly different in texture, follows the same thematic logic: a man enters a place, thinks he knows it, and is undone by the truth beneath its surface.

If Vivarium was Finnegan’s Orwellian satire, then The Surfer is his Camus novel. There’s something relentlessly existential about the heat, the horizon, and the quiet unraveling of Cage’s character. There are no jump scares. No monsters in the dark. The terror is the clarity—the way everything is visible under the sun, but nothing is understood. Like Meursault in The Stranger, The Surfer is estranged not only from society but from himself.

Finnegan crafts this estrangement with slow pacing, minimal dialogue, and oppressive cinematography. The lens lingers on sweat, on waves, on the slow fry of flesh and ego. The beach becomes a war zone of passivity. No escape. No climax. Only the inevitable rot of a man stripped of myth.

Nicolas Cage: From Folk Hero to Folly

This role is tailor-made for Cage. He has long lived in the borderlands of performance—part Shakespearean tragedian, part mad prophet, part absurdist. In The Surfer, he is all three. But crucially, this is not a loud Cage performance. It’s not Mandy. It’s not Vampire’s Kiss. It’s something quieter. More pitiful. More unsettling in its restraint.

The brilliance of Cage’s portrayal lies in the way he holds his collapse. He’s not becoming mad. He’s already there. What we watch is the slow surfacing of that madness—like a bruise rising beneath tanned skin. There are moments of eruption, yes—a primal scream here, a self-mutilation there—but mostly it is a performance of erosion. Of sweat, shame, and heatstroke hallucinations.

What’s fascinating is that Cage does not try to reclaim the beach. He doesn’t fight the local surf tribe with bravado. He simply refuses to leave. He camps out. Sleeps rough. Watches. Waits. His power is in his stubbornness, his madness. He is not a man trying to reclaim his past glory—he is a ghost haunting the sand. And as the film goes on, you begin to wonder: is this even real? Or is The Surfer dead already, caught in some purgatory of salt and sun?

The Beach as Battlefield: Territorialism and Surf Folklore

Surf culture has always flirted with contradiction. It sells itself as freedom—waves, wilderness, the open horizon—but in reality, it’s often fiercely territorial. Localism is not just a social dynamic; it’s an unspoken law. And in The Surfer, that law becomes the foundation of violence.

The gang that ejects Cage from the surf break is not simply a bunch of beach punks. They are, in a strange way, archetypes—like the Wild Boys from Mad Max or the Lost Boys from Peter Pan, if they were armed with surfboards and meth aggression. They don’t just want the waves. They want submission. They want dominance. They are the mythic sons of a decaying masculinity—products of heat and sand and an economy where manhood is earned through cruelty.

Cage’s character, in contrast, is a relic. A middle-aged man trying to hold on to a childhood haunt, a washed-up father with nothing left to fight for but pride. The tension between these two generations—one fading, one feral—is at the core of the film’s drama.

Finnegan shoots the surf scenes with a sense of ritual. The waves are never just waves. They’re trials. They’re tests. To surf here is not leisure—it’s proving you belong. And Cage, stripped of his welcome, becomes something between a prophet and a trespasser. His very presence is an affront.

Heatwave Cinema: The Thermodynamics of Breakdown

Much like Dog Day Afternoon, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, or Walkabout, The Surfer belongs to the lineage of “heatwave cinema.” These are films where the environment becomes a co-conspirator in madness. Heat becomes a narrative device. The sun isn’t just hot—it’s hostile. And in The Surfer, it’s omnipresent.

The color palette bleaches out over time—bright whites, scorched sand, the glare of the ocean at noon. Shadows shorten. Sweat drips. Skin peels. The heat is invasive. It eats through logic. It hallucinates. And Finnegan uses this to create a kind of temporal drift. Time slows. Days melt. You lose track of chronology. Is this Day 3? Day 7? Or has Cage been on that beach for years, slowly dissolving into the landscape?

Cinematographer Stefan Duscio captures this dissolution with savage grace. Every frame is overexposed just enough to feel sickly. There’s no relief. Even nighttime scenes feel suffocated by residual heat. This isn’t just sunburn. It’s soul-burn. A man liquefied by light.

Dialogue and Minimalism: A Film of Silences

The Surfer is a film of long silences and short, clipped confrontations. The dialogue—when it comes—is terse, ritualistic, and often surreal. Cage mutters to himself. The gang speaks in half-jokes and veiled threats. There’s a monotony to the language, a sense that meaning is leaking out like sweat.

This is intentional. Finnegan is not interested in plot so much as stasis. The conflict doesn’t escalate in the traditional sense. It loops. It festers. And the power of the film lies in its refusal to resolve.

In many ways, this is a horror film without horror, a revenge film without revenge. There’s no catharsis. No victory. Just a man, the sea, and the slow grind of ego under erosion.

Existential Parable or Environmental Allegory?

There are several ways to read The Surfer. As an existential character study, it fits neatly into the tradition of The Lighthouse, Repulsion, or even No Country for Old Men. But it’s equally valid to read it as an environmental allegory.

Cage’s character is, after all, a man who refuses to adapt. He clings to the past. He camps on contested land. He refuses to leave even when asked. He consumes. He stagnates. One could argue he is the problem. The film never tells us if he deserves sympathy. And that ambiguity is its strength.

The beach is not his to reclaim. The waves do not remember him. The world has moved on. And in that sense, The Surfer becomes a quiet indictment of nostalgia as a toxic impulse. The past doesn’t want us back. Especially not if we arrive with tan lines and entitlement.

Impression

The Surfer is not a film that rides high. It crouches. It watches. It waits. It refuses to give you what you want—a climax, a confrontation, a clean redemption. Instead, it hands you a sunburn and a question: What happens to the men who cannot leave the places that no longer want them?

Lorcan Finnegan has created something rare here—an anti-surf film, a heatwave parable, a Cage performance that is equal parts martyr and mirage. It is a story that bakes into your brain. Not a wave to ride, but one to drown in.

And when the credits roll, you may find yourself parched, disoriented, and strangely haunted. Because The Surfer doesn’t let you leave the beach. It drags you under. Holds you there. Until you, too, are just another ghost in the tide.

No comments yet.