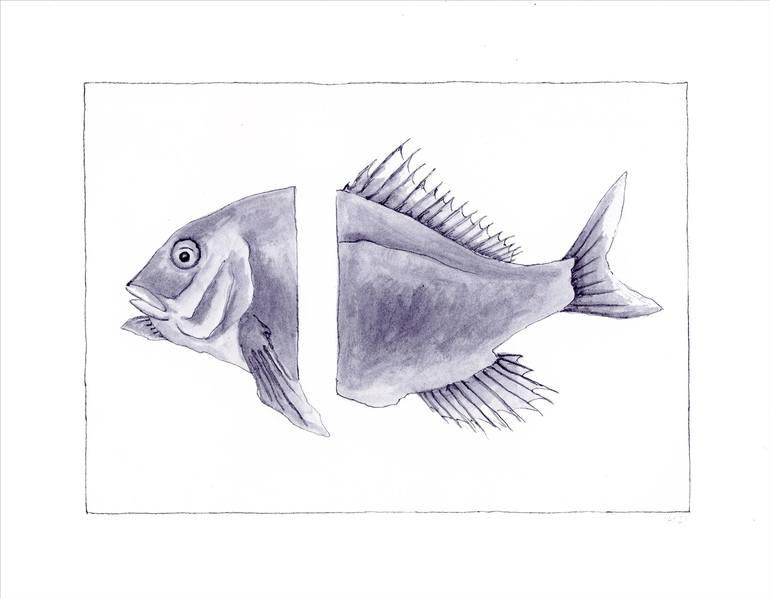

In an age saturated with digital maximalism and visual noise, the minimal, precise works of Marianne Hendriks feel like a whisper that cuts through a crowded room. The Netherlands-based artist has long explored themes of form, repetition, and the uncanny in everyday objects. Her piece Cut Fish Drawing is no exception. Rather than a simple still life, it is a meditation on nature, consumption, and the hidden geometries of life itself.

At first glance, Cut Fish Drawing might appear to be a straightforward study of a fish, dissected and arranged with clinical precision. But upon deeper engagement, it reveals itself as a layered commentary on our relationship with the natural world and the aestheticization of consumption.

A Historical Lineage of Still Life and Nature Morte

To truly understand Hendriks’s approach, we must first look at the genre of still life — particularly “nature morte,” or “dead nature,” as the French call it. Originating in the 16th and 17th centuries, especially in Dutch Golden Age painting, still life works often depicted inanimate objects: fruit, flowers, game, and, frequently, fish.

These paintings were more than decorative indulgences. They often carried moral undertones, reminding viewers of the fleetingness of life (vanitas) and the temporality of material pleasures. Fish, in particular, held symbolic meaning: sometimes associated with Christianity and resurrection, at other times simply markers of abundance and trade wealth in Northern Europe.

Hendriks’s Cut Fish Drawing carries forward this lineage but distills it into a modern idiom. She strips away the rich oil textures, golden goblets, and lavish table settings typical of historical still lifes. Instead, she offers crisp, almost surgical lines on paper — evoking both scientific illustration and minimalist design.

Form as Narrative

One of the most striking aspects of Cut Fish Drawing is its focus on form and division. By slicing the fish and presenting it as though each segment is laid out for analytical study, Hendriks shifts our perception. The fish ceases to be a singular organic being and becomes a series of abstracted parts.

This approach recalls the tradition of natural history illustration, where specimens were meticulously drawn for study rather than aesthetic pleasure. It also nods to the Bauhaus and De Stijl movements, where abstraction and the reduction of forms were pursued to reveal universal truths in design and art.

The sense of flatness and precision in Hendriks’s work challenges our idea of what is “alive” in a picture. It invites the viewer to engage analytically rather than emotionally — yet paradoxically, in doing so, it forces a deeper emotional reflection on the object itself.

The Uncanny in the Everyday

Marianne Hendriks is known for finding the uncanny in mundane forms. Whether drawing houseplants, architectural elements, or marine life, she deconstructs them into their fundamental lines and curves.

Cut Fish Drawing fits squarely into this practice. A fish — a common symbol of domesticity, diet, and simplicity — becomes unsettling when rendered in stark, dissected fragments. There is a cold beauty to the piece, a kind of serene violence that echoes in our consciousness long after viewing.

Hendriks’s work pushes us to question what lies beneath surface appearances, not just in art but in life. What do we consume without truly seeing? What beauty do we overlook because it is too familiar, too utilitarian?

Literary Echoes: The Poetics of Dissection

In literature, fish have served as powerful metaphors, from Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea to Sylvia Plath’s visceral poems. The act of cutting or dissecting is often associated with revealing hidden truths — a metaphorical unveiling of inner life.

Cut Fish Drawing resonates with this literary tradition. The fish, sliced open, stands not just for consumption but for revelation. There is a quiet, poetic violence in turning an organic whole into intellectual parts. Hendriks invites us to contemplate the balance between destruction and understanding — how in dissecting, we often lose the soul of the thing we seek to know.

From Dutch Realism to Contemporary Minimalism

Dutch artists have a rich history of capturing the minutiae of daily life with near-scientific accuracy. From Vermeer’s intimate interiors to the intricate flower studies of Rachel Ruysch, there has always been a fascination with the interplay of the ordinary and the sublime.

Hendriks takes this tradition and runs it through a minimalist, almost algorithmic filter. Her lines are so precise they could be mistaken for digital renderings. Yet the hand-drawn quality remains, creating a tension between mechanical repetition and human imperfection.

Recent Trends: The Rise of Hyper-Analytical Art

In recent years, there has been a surge in art that leans into analysis, precision, and process. As we grapple with big data and AI-driven design, many artists have turned to meticulous methods to explore ideas of control, identity, and perception.

Hendriks’s work aligns with this trend while retaining a deeply personal aesthetic. Her fish is not merely an object of study; it becomes a symbol of how we dissect our world, our relationships, and even our own selves in the pursuit of understanding.

A Meditation on Consumption

At a more immediate level, Cut Fish Drawing also engages with ideas of consumption — literal and metaphorical. In our age of overconsumption, a neatly sliced fish becomes a potent image. It speaks to our compartmentalization of nature, our detachment from the origins of what we consume.

The drawing quietly critiques how we package, slice, and present nature to suit aesthetic and dietary preferences, transforming life into commodity.

A Global Context: Dutch Art in the Contemporary Sphere

Marianne Hendriks operates within a global art dialogue but remains deeply connected to her Dutch roots. Contemporary Dutch artists have long excelled at merging tradition with modernity, from the conceptual provocations of Marlene Dumas to the subtle narratives of Michael Raedecker.

Hendriks’s focus on reduction and form positions her within a new generation of artists looking beyond figurative realism to explore the metaphysical dimensions of seeing.

Viewer as Participant

Unlike loud, immersive installations, Hendriks’s works require quiet contemplation. The viewer must slow down, consider each line, each division. In a world of constant stimuli, her art demands patience, a return to the slow gaze.

This participatory aspect elevates Cut Fish Drawing from mere image to experience. It is not art to be consumed quickly but to be absorbed, lived with, and re-interpreted over time.

An Invitation to See Differently

In Cut Fish Drawing, Marianne Hendriks offers more than a visual representation of a fish. She offers a meditation on the act of seeing itself. By dissecting the form, she constructs a new anatomy of perception — one where familiarity is undone and reassembled into something at once scientific and poetic.

Her work is a reminder that even in the most mundane subjects, there lies a universe of possibility and complexity. In a time when art is often expected to shout to be heard, Hendriks chooses to whisper, trusting that those who truly look will find infinite stories within her delicate lines.

No comments yet.