David Voss’s art fraud scheme stands as one of the most notorious and impactful scandals in modern art history, not merely for its financial implications, but for the cultural and ethical devastation it caused. Voss allegedly orchestrated the sale of over $50 million worth of forged artworks, a crime that deeply affected both private collectors and public institutions. His operation serves as a cautionary tale about the vulnerabilities of the art market, where trust, provenance, and expertise are often manipulated for financial gain. This critical explication will explore the intricacies of Voss’s scheme, the cultural impact of art fraud, and how his case reflects broader issues of authenticity, value, and exploitation in the art world.

The Art of Deception

The sheer scale of Voss’s operation is staggering. The fact that his network successfully passed off fraudulent works attributed to some of the most famous artists of the 20th century—Picasso, Monet, and Rothko—speaks to the sophistication of the forgeries and the depth of the deception. Art forgery is not a new crime; it has existed for centuries. However, what made Voss’s scheme particularly troubling was its ability to exploit weaknesses at multiple levels of the art ecosystem, including collectors, galleries, auction houses, and even experts.

A key component of his fraud was the creation of counterfeit certificates of authenticity, which allowed these fake artworks to be seen as legitimate. The art market relies heavily on provenance, or the documented history of ownership, to verify the authenticity of a work. Voss’s ability to manipulate this process, along with his recruitment of skilled forgers, allowed him to dupe buyers into believing that they were purchasing genuine masterpieces. This type of fraud exploits not only the financial investment of collectors but also their emotional and intellectual investment in the art itself. For many buyers, art is not merely a commodity; it is a cultural artifact with deep personal and historical significance.

The Vulnerability of the Art Market

Voss’s case highlights a significant vulnerability in the art market: the reliance on a relatively small group of experts and intermediaries to verify authenticity. Many of the buyers in Voss’s scheme were wealthy collectors eager to acquire rare and valuable pieces. These individuals often placed their trust in art dealers and auction houses, assuming that due diligence had been performed. Voss and his associates exploited this trust by infiltrating these networks, using their knowledge of the art world to target individuals who were more focused on expanding their collections than on verifying the authenticity of each piece.

The art world’s elitism and secrecy also played a role in the success of the scheme. Art transactions, particularly in the high-end market, are often conducted privately, with little public oversight. This lack of transparency creates opportunities for fraudsters to operate undetected for extended periods. In Voss’s case, the intricate network of forgers, dealers, and buyers he built was able to function in the shadows for years before investigators uncovered the scheme.

Impression

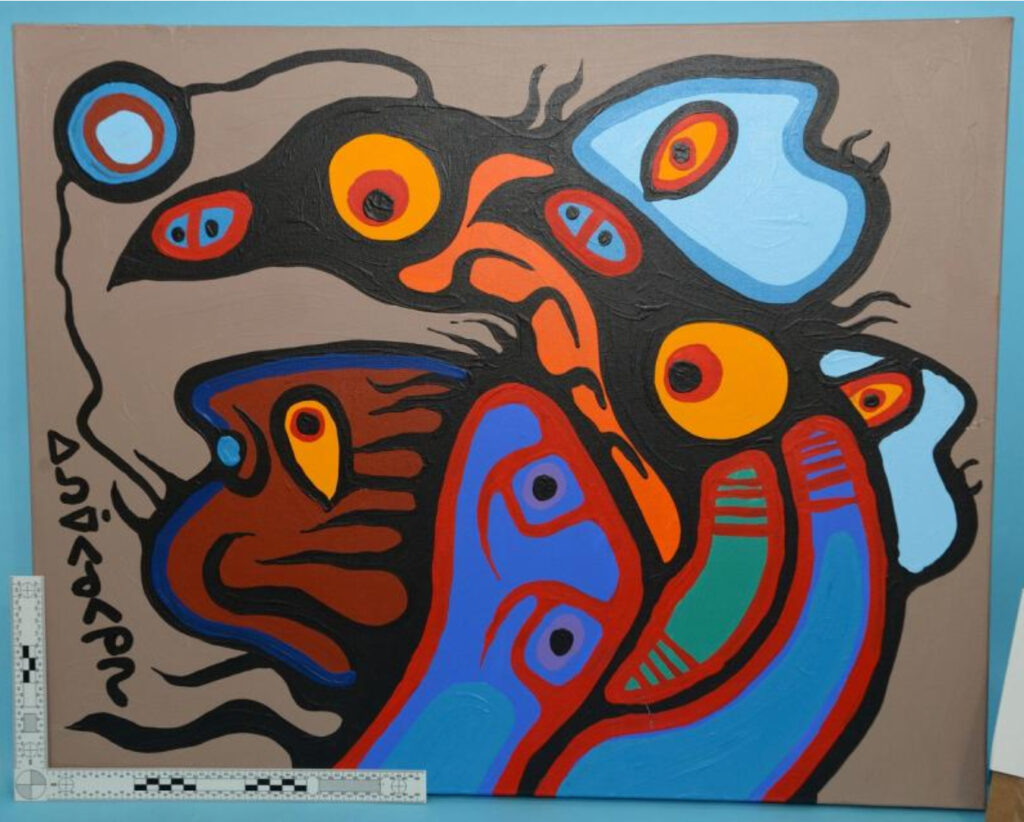

While the financial losses caused by Voss’s scheme were substantial, the cultural damage was perhaps even more profound. Among the artists whose works were forged was Norval Morrisseau, a celebrated Indigenous Canadian artist known for his vibrant, spiritual depictions of Anishinaabe culture. Morrisseau’s art carries deep cultural significance, particularly for Indigenous communities. By forging Morrisseau’s work, Voss not only defrauded collectors but also undermined the cultural integrity of an important artist’s legacy.

Morrisseau’s art is not merely decorative; it is imbued with cultural and spiritual meaning, representing a visual language that connects the artist’s personal experience with broader Indigenous traditions. Forgeries of his work represent a form of cultural appropriation and exploitation, as they commodify and cheapen the very heritage Morrisseau sought to preserve and elevate. By imitating Morrisseau’s style for profit, Voss’s operation engaged in a form of cultural vandalism, reducing works of profound significance to mere transactions in a fraudulent marketplace.

The cultural implications of this forgery reach beyond the immediate financial harm to collectors. It raises questions about the ethics of art ownership and the responsibilities that come with collecting works that carry cultural and historical weight. In Morrisseau’s case, the sale of fake paintings not only harmed collectors financially but also contributed to the erasure of authentic Indigenous voices in the art world, diluting the market with false representations of their artistic traditions.

The Ethics of Art Fraud

At its core, art fraud is a crime that undermines the very foundations of the art world: authenticity, value, and trust. Forgeries like those produced in Voss’s scheme challenge the notion of what makes art valuable. Is it the aesthetic experience of viewing the work? The artist’s unique touch? The cultural or historical significance of the piece? Or is it simply the financial investment tied to the artist’s name?

Voss’s operation capitalized on the idea that much of the art world’s value is tied to perceived scarcity and the reputations of renowned artists. Collectors were willing to pay millions for what they believed to be rare works by Picasso or Monet, not only because of the aesthetic qualities of the paintings but because owning these works conferred status and financial security. By injecting forgeries into this system, Voss revealed how fragile these assumptions about value and authenticity can be.

This case also raises ethical questions about the role of forgers and the motivations behind art fraud. Forgers are often highly skilled artists in their own right, capable of replicating the techniques and styles of history’s greatest painters. While their actions are undoubtedly criminal, they also highlight the tension between the art world’s reverence for individual genius and its dismissal of technical skill when it comes to lesser-known or anonymous artists. Voss’s forgers were able to produce works that fooled experts, yet their talents were only recognized within the context of deception. This dichotomy invites a broader discussion about the nature of artistic talent and the ways in which the art market values, or fails to value, different types of artistic contributions.

A Cautionary Tale

David Voss’s art fraud scheme stands as a powerful reminder of the need for greater scrutiny and transparency in the art world. It exposed the weaknesses in a system that often prioritizes financial gain over cultural integrity and demonstrated the dangers of placing too much trust in the hands of a few intermediaries. Beyond the financial losses, Voss’s forgeries damaged the reputations of artists and institutions, while also contributing to the erasure of authentic cultural voices like Norval Morrisseau.

As the art market continues to evolve, cases like Voss’s should serve as a catalyst for change. Greater emphasis on provenance, transparency, and ethical collecting practices can help prevent future frauds and ensure that the value of art is based on its true cultural and aesthetic significance, rather than on deception and exploitation.

No comments yet.