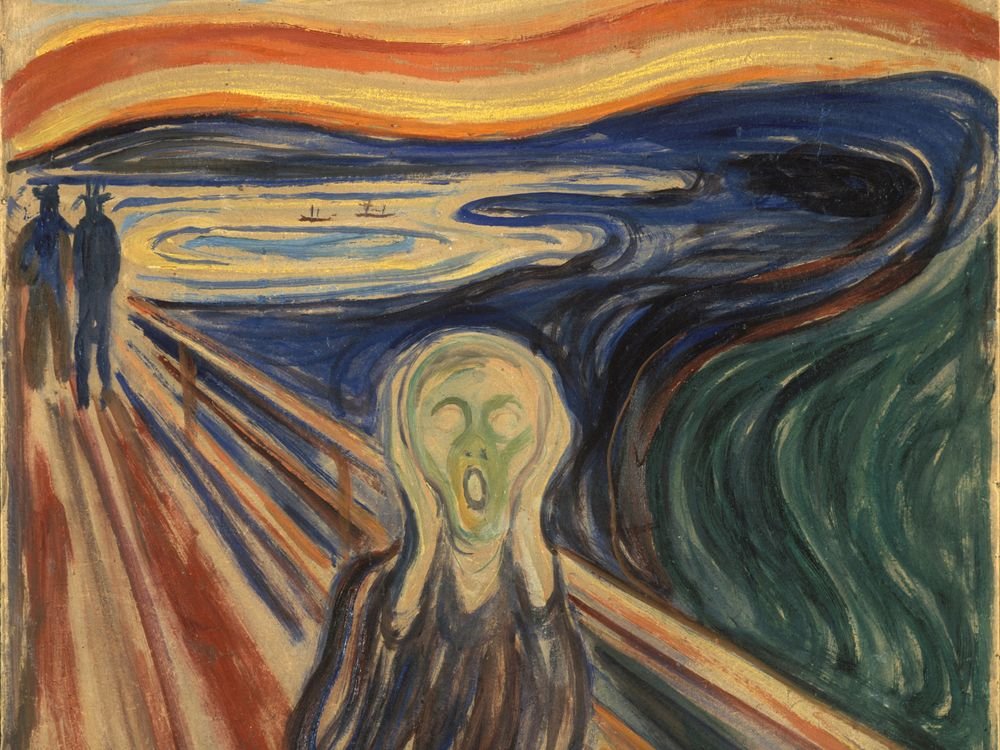

Born on December 12, 1863, Edvard Munch emerged as one of the most enigmatic figures in the history of art, leaving behind a legacy that continues to intrigue art lovers and scholars alike. His most famous work, The Scream, has become an emblem of modern existential anguish, its haunting figure a silent scream against the void. However, Munch’s contributions to art extend far beyond this singular masterpiece. Through his extensive body of work, he explored themes of anxiety, death, alienation, and unrequited love, offering a deeply personal glimpse into the psyche of a man grappling with inner demons.

Early Life: A Family Marked by Tragedy

Edvard Munch was born in Loten, Norway, to Christian Munch, a devoutly religious military doctor, and Laura Catherine Bjølstad. The Munch family’s life was steeped in tragedy. Laura died of tuberculosis when Edvard was just five years old, and his older sister Sophie succumbed to the same disease nine years later. Another sister, Laura, struggled with mental illness, and his brother Andreas died shortly after marriage.

These early experiences of illness and death cast a long shadow over Munch’s childhood and profoundly shaped his worldview. His father’s intense piety compounded the young boy’s anxieties, as Christian Munch often invoked religious imagery and punishment. In an autobiographical note, Munch once wrote, “Illness, insanity, and death were the black angels that kept watch over my cradle.”

This pervasive sense of mortality and despair would later dominate his artistic themes, creating a distinctive style that sought to unravel the complexities of human existence.

The Rise of an Artist: The Road to Expressionism

Munch initially pursued engineering but abandoned the field in favor of painting in 1880. He enrolled at the Royal School of Art and Design in Kristiania (now Oslo), where he encountered naturalism and impressionism. Early works such as The Sick Child (1885–86) reveal his budding interest in themes of grief and suffering, influenced by his sister Sophie’s death.

In 1889, Munch received a scholarship to study in Paris. While there, he was deeply influenced by the works of French Symbolists such as Paul Gauguin and the writings of Charles Baudelaire. Gauguin’s use of bold colors and emotional intensity struck a chord with Munch, inspiring him to abandon realism for a more evocative and symbolic style.

Munch’s travels across Europe exposed him to emerging movements, particularly Symbolism and Post-Impressionism. His work began to integrate these influences, paving the way for what would later be called Expressionism.

The Frieze of Life: A Cycle of Human Emotions

Munch’s seminal project, The Frieze of Life, is a collection of works exploring love, anxiety, death, and despair. Painted between 1893 and 1918, this series captures the emotional highs and lows of human existence through striking symbolism and vibrant colors.

Key works from The Frieze of Life include:

•The Scream (1893): Perhaps the most iconic painting of the modern era, The Scream depicts a solitary figure on a bridge, consumed by existential dread. Munch described the inspiration for the work as a moment when he felt “a great infinite scream pass through nature.” The swirling sky and distorted figure encapsulate a profound sense of alienation and anxiety.

•Madonna (1894–95): A provocative portrayal of femininity, Madonna contrasts themes of sensuality and spirituality. The figure, surrounded by an aura of flowing lines, symbolizes both the giver of life and the inevitability of death.

•The Dance of Life (1899–1900): This work portrays the stages of love, from youthful passion to despair and loneliness, reflecting Munch’s fraught romantic experiences.

Through The Frieze of Life, Munch captured universal emotions while simultaneously revealing his personal struggles, particularly his battles with mental health.

Mental Health Struggles and Isolation

Munch’s personal life was marked by instability and isolation. He never married, and his relationships were often tumultuous. A failed romance with Tulla Larsen in the early 1900s left him deeply scarred, as did the guilt and regret associated with his family’s tragedies.

By 1908, Munch’s mental health deteriorated significantly, culminating in a breakdown. He was admitted to a sanatorium, where he received treatment for hallucinations and severe anxiety. Munch later credited this period of convalescence with helping him regain stability and focus, but his art remained a reflection of his inner turmoil.

His later works became more subdued, focusing on landscapes and portraits that conveyed a quieter, melancholic beauty.

Artistic Techniques: Symbolism Meets Expressionism

Munch’s artistic techniques were as innovative as his themes. His style evolved from naturalism to a highly emotional, symbolic language that prioritized mood over realism.

•Color as Emotion: Munch used vivid, sometimes jarring colors to convey psychological states. The fiery reds in The Scream, for example, heighten the sense of panic and dread.

•Distorted Forms: To capture inner turmoil, Munch often distorted figures and landscapes. This technique, evident in works like Anxiety (1894), emphasized the emotional over the literal.

•Symbolic Imagery: Munch’s paintings are rich with recurring motifs, such as flowing lines, swirling skies, and shadowy figures. These elements create a dreamlike, almost surreal quality.

His approach laid the foundation for Expressionism, a movement that sought to convey subjective emotions and inner experiences rather than objective reality.

Legacy: Influence on Modern Art

Edvard Munch’s influence on modern art is immeasurable. His exploration of psychological themes and innovative techniques inspired generations of artists, including the German Expressionists and the Abstract Expressionists.

Artists such as Egon Schiele and Wassily Kandinsky drew from Munch’s emotive use of color and form, while his focus on the human condition resonated with later figures like Francis Bacon.

Munch’s work also extends beyond the fine arts. The haunting imagery of The Scream has permeated popular culture, appearing in films, literature, and even emojis. It remains one of the most recognizable symbols of existential angst.

Controversies and Art Theft

The enduring appeal of Munch’s work has made it a target for art thieves. The Scream has been stolen multiple times, most famously in 1994 and 2004. While the paintings were recovered, these incidents highlight the global fascination with Munch’s art.

Additionally, his unconventional techniques and subject matter sparked controversy during his lifetime, with critics often dismissing his work as morbid or overly dramatic. Yet, these very qualities have ensured his lasting relevance in the art world.

Later Years and Death

In his later years, Munch retreated to a secluded estate in Ekely, Norway, where he continued to paint until his death. His later works, often overshadowed by his earlier masterpieces, include serene landscapes and introspective self-portraits.

Edvard Munch passed away on January 23, 1944, leaving behind an extensive collection of over 1,000 paintings, 4,000 drawings, and 15,000 prints. His home and studio were later transformed into the Munch Museum in Oslo, which houses the largest collection of his works.

Conclusion: An Artist of the Human Soul

Edvard Munch’s art remains a testament to the complexity of human emotion and the transformative power of creativity. Through his exploration of themes like anxiety, love, and mortality, he offered a deeply personal yet universally relatable vision of the human experience.

The Scream may be his most famous work, but Munch’s broader oeuvre reveals an artist unafraid to confront the darker aspects of life. His legacy endures not only in the art world but also in the cultural imagination, reminding us of the resilience of the human spirit in the face of despair.

Munch’s life and work embody the belief that art can serve as both a mirror and a balm, reflecting our innermost fears while offering solace in shared understanding. For this reason, his paintings continue to resonate, their emotional intensity undiminished by time.

No comments yet.