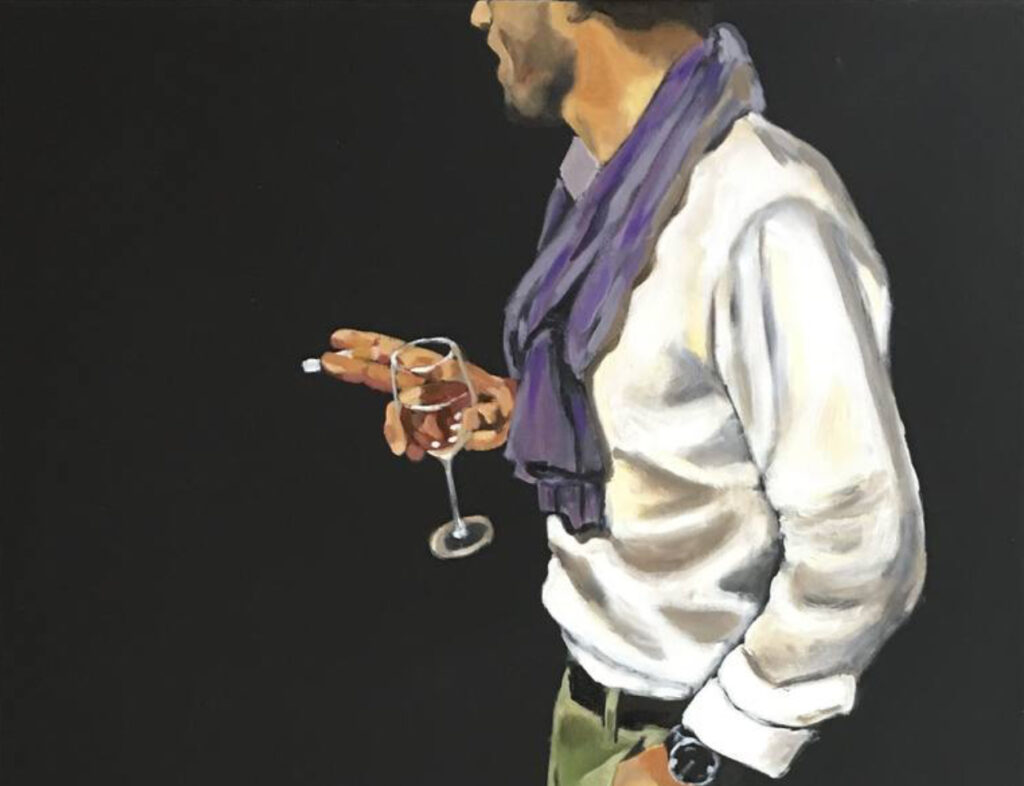

In the work of French artist Yuna Bert, conversation becomes composition, and silence, a medium just as potent as oil. Her painting “Men Talk II”, rendered in a sweeping, vulnerable dialect of oil on canvas, confronts one of the quietest revolutions of the modern era: the shifting interior lives of men. Neither polemic nor pastiche, “Men Talk II” is a study of masculinity stripped of bravado, reduced instead to the simple, radical act of presence.

In an art world still wrestling with how to depict the masculine subject without veering into parody or perpetuation, Bert’s piece is a testament to the transformative power of empathy and observation. It is a painting that does not shout but hums, insistently and intimately, into the spaces between men—their exchanges, their hesitations, their unseen negotiations of power and vulnerability.

The Composition: A Frame within Frames

At first glance, “Men Talk II” presents a simple scene: two men, seated across from each other in an undefined but intimately scaled space, engaged in conversation. But the more one gazes, the more the canvas opens up like a novel—layer after layer of emotional architecture unfolding from small gestures and suspended gazes.

Bert’s composition is spare, yet masterfully weighted. The two figures are positioned slightly off-center, their bodies forming a subtle axis that pulls the viewer’s eye back and forth, in silent mimicry of their dialogue. The background is muted but not void; Bert uses tonal gradations of earthen colors to imply walls, perhaps a window, a suggestion of a table—but these elements dissolve into abstraction at the periphery, emphasizing the psychological space over the physical.

There is no crowd, no bustling city outside the frame. Only these two men, and the charged silence between them.

Oil as Language

Bert’s use of oil on canvas is itself a kind of conversation—a dialogue between control and surrender. Her brushwork oscillates between precision and blur, as though mimicking the slippery nature of spoken word: how sentences are often started and abandoned, how meaning pools in pauses more than in phrases.

The figures are rendered with a quiet realism, but they are not hyper-detailed. Their faces, particularly, are notable for their restraint. Bert refuses the lure of photographic likeness. Instead, their expressions are half-formed, half-erased, allowing viewers to project their own interpretations onto the scene. What matters is not the specific identity of the men, but the space they occupy together—the relational energy Bert captures with painterly sensitivity.

Colors bleed slightly into each other at the edges of the figures, a technique that serves both to unite them and to suggest the permeability of their individual identities. In conversation, they seem to shape each other, if only momentarily.

Masculinity Reimagined

“Men Talk II” exists within a crucial conversation in contemporary art about the portrayal of male intimacy. For centuries, Western art treated men as either heroic figures, eroticized subjects, or symbols of stoic autonomy. Rarely were men depicted simply talking—sharing space without overt competition or spectacle.

Bert’s painting stands in quiet defiance of these historical patterns. The two men are neither idealized nor diminished. They are not athletes, soldiers, or kings. They are simply two human beings, navigating a moment together. Their vulnerability is not dramatized; it is normalized.

In doing so, Bert offers a profound, if understated, critique of traditional masculinity: its enforced silences, its armored performances, its fear of tenderness. She does not mock these men for having a conversation; she venerates them for it. She paints male vulnerability without fetishizing it, and without turning it into tragedy.

The Silence Between Words

Perhaps the most compelling feature of “Men Talk II” is what it leaves unsaid. The painting is saturated with suggestion: what are these men discussing? Are they friends, lovers, colleagues, strangers? Is this a negotiation, a confession, a reconciliation?

Bert provides no easy answers. Instead, she positions the viewer as an interloper, tasked with deciphering a language made up of small physical cues: the tilt of a shoulder, the flex of a hand, the angle of a chin. In this way, the viewer becomes a third participant in the conversation, trying to intuit meaning from the silent choreography of bodies.

This ambiguity invites empathy. To engage with the painting is to imagine the lives of others—to fill in the gaps not with certainty, but with curiosity and care. It is, in essence, an exercise in emotional imagination.

French Lineage and Contemporary Tensions

As a French painter, Yuna Bert inherits a complex artistic tradition. France has long been a crucible for explorations of human connection—from the romantic melancholy of Delacroix to the existential interrogations of Giacometti. Yet Bert’s work feels distinctly contemporary in its concern with gendered communication and emotional nuance.

Unlike the grand narratives of 19th-century history painting, or even the alienation often depicted in mid-20th century existentialist works, “Men Talk II” insists on smallness as a virtue. This is not history at its loudest; it is humanity at its quietest.

There are echoes, perhaps, of Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot’s muted palettes, or even the psychological interiors of Édouard Vuillard. But Bert is not interested in stylistic homage. She wields the tools of the French tradition with a clear-eyed awareness of the 21st century: a time when the politics of gender, language, and vulnerability are being rewritten in real time.

Emotional Architecture: Space and Body

Beyond its thematic brilliance, “Men Talk II” is a study in spatial mastery. Bert uses negative space like a sculptor: shaping absence into presence. The canvas feels both full and spare, heavy with what is not shown.

The men’s bodies occupy more emotional space than physical. The slight lean forward of one figure suggests an opening; the guarded crossing of arms by the other hints at a defensive posture. These micro-gestures serve as the true architecture of the scene. There are no grand movements, no dramatic flourishes—just the slow, tidal rhythms of human connection being built, dismantled, and rebuilt.

A Mirror for the Viewer

In its quiet brilliance, “Men Talk II” becomes a kind of mirror. It reflects not just the scene on the canvas, but the emotional state of the viewer. What one sees in the painting—the possibility of confrontation, confession, camaraderie—is a function of one’s own emotional lexicon.

This reflexivity is part of what makes Bert’s work so resonant. She does not dictate meaning; she facilitates it. “Men Talk II” is not a lesson. It is an offering.

Impression

“Men Talk II” by Yuna Bert is not a painting that can be consumed in a glance. It resists the speed of contemporary image culture. Instead, it demands that we slow down, look closer, and listen—not with our ears, but with our empathy.

In an age when masculinity is being redefined and renegotiated across cultural spheres, Bert’s painting offers a vision not of collapse, but of quiet revolution. Here, masculinity is neither scorned nor sanctified. It is simply human—complex, tentative, striving toward better articulation.

In oil and canvas, Yuna Bert has done what even language often struggles to achieve: she has captured the fragile, resilient truth that between men, sometimes the most radical act is simply to talk.

No comments yet.