PAPER CUT doesn’t greet you like an exhibition. It ambushes you. The gallery has been transformed into something closer to a children’s art table left unattended too long: crayons scattered without hierarchy, glue sticks rolling underfoot, paper curling at the edges, colours clashing freely. It is messy, bright, fragile, and instantly disarming. Before you can intellectualize it, the space pulls you into a memory—of floors protected with old newspapers, of hands sticky with paste, of making something without caring whether it would last.

Created by PRIEST, PAPER CUT uses this language of childhood play not as nostalgia, but as method. The installation reimagines play as a form of social archaeology, excavating the hidden layers of contemporary London through materials that are usually dismissed as unserious. Popsicle sticks, macaroni, pipe cleaners, cardboard—these are not metaphors imported from theory. They are the tools themselves. And they build a world that feels funny at first, then increasingly uncomfortable.

Among the sprawl, objects emerge and dissolve into one another. An abandoned popsicle-stick house leans precariously, its structure fragile enough to collapse with a breath. A life-size diorama stretches across the room, part model village, part stage set, its scale refusing to settle. Macaroni paintings cling to the walls, their pasta shells yellowed, cracked, and unevenly glued, more vulnerable than decorative. Pipe-cleaner figures appear mid-gesture—arms raised, bodies twisted—frozen between intention and accident.

style

PRIEST’s installation borrows the visual grammar of childhood but refuses the sentimentality that usually accompanies it. These are not cute objects. They are unstable ones. The popsicle-stick house reads immediately as housing—temporary, improvised, inadequate. In London, that reading is unavoidable. The housing crisis is not illustrated; it is embedded in the structure itself. Cheap materials. Shaky foundations. A sense that shelter is provisional, always one movement away from collapse.

The life-size diorama amplifies this unease. Its scale pulls the viewer inside rather than allowing the safety of observation. You are no longer looking at a model of a city; you are walking through a child’s approximation of one. Streets don’t align. Buildings feel copied rather than designed. Familiar forms repeat with slight variations, like imitations of imitations. It mirrors how the city itself often feels now—endlessly replicated developments, aesthetic sameness masking social fragmentation.

stir

Macaroni paintings, often the first “artworks” a child is praised for, hang awkwardly, neither ironic nor reverent. They suggest labour without mastery, effort without polish. In the context of contemporary art culture—where professionalism, branding, and strategy dominate—their presence feels almost confrontational. They ask an uncomfortable question: when did art stop being allowed to look like this? When did sincerity become embarrassing?

Pipe-cleaner figures bring another register entirely. Bent, colourful, almost cartoonish, they appear frozen in acts that could be dancing, fighting, posing, or collapsing. It’s impossible to say. That ambiguity echoes the way youth culture is often read through adult panic and projection. Youth violence, influencer culture, performative masculinity, vulnerability turned into spectacle—these themes surface not through explicit imagery, but through posture. Bodies caught mid-performance, unsure whether they are being watched or ignored.

Beneath the colour, London is everywhere. Not as skyline or landmark, but as pressure. The weary humour of modern life runs through the installation like a low current. The jokes are visual, but they don’t land cleanly. They linger. The humour feels defensive, a coping mechanism rather than a punchline. You laugh, then wonder why you did.

PRIEST’s decision to frame the work as a table—rather than walls, plinths, or screens—is crucial. A table is a place of making, but also of gathering, negotiation, and hierarchy. In childhood, the table is where rules are temporarily suspended. In adulthood, it’s where decisions harden. PAPER CUT collapses those meanings, turning the gallery into a site where play and power coexist uncomfortably.

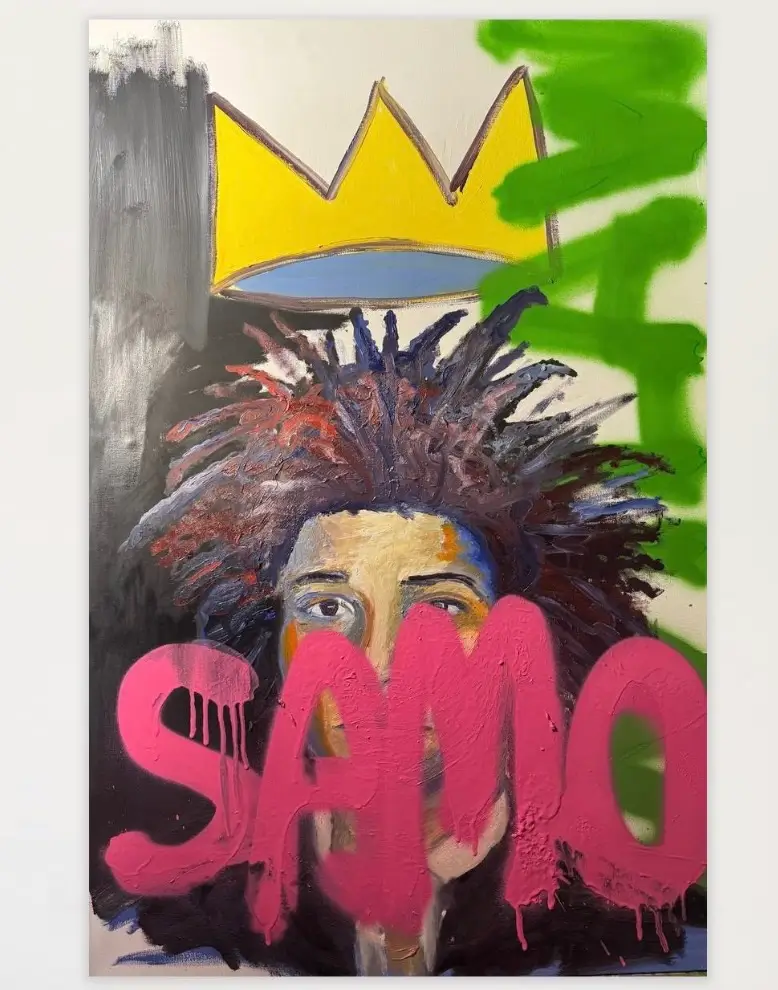

idea

PAPER CUT suggests that as art professionalizes, something essential is lost. Spontaneity becomes strategy. Honesty becomes a pose. Risk is managed, sanitized, insured. Even rebellion develops a brand voice. The installation’s refusal of polish is not an aesthetic choice alone—it’s an ethical one. By working with fragile materials and deliberately amateur techniques, PRIEST resists the expectation that art should arrive already resolved.

There is also an implicit critique of influencer culture woven throughout the space. The repetition of forms, the exaggerated gestures of the figures, the sense of constant display all point toward a culture obsessed with visibility. Childhood play is usually private or semi-private, valued because it doesn’t need an audience. In contrast, adult creativity increasingly assumes one. PAPER CUT exposes the strain of that shift. These objects look like they might fall apart if watched too closely.

Yet the exhibition never fully condemns adulthood. Instead, it asks whether the child who first picked up the crayon might have understood something we’ve since complicated beyond recognition. Children don’t ask whether their work is “relevant.” They don’t worry about coherence or legacy. They make because making feels necessary. In that sense, PAPER CUT is less a lament than a provocation.

impression

The answer, PRIEST seems to suggest, is not to return to childhood, but to learn from it. To accept mess as meaningful. To allow failure to remain visible. To acknowledge that imitation, chaos, and contradiction are not flaws in culture but features of it—especially in a city like London, where identities are constantly assembled from borrowed parts.

PAPER CUT does not offer solutions. It offers surfaces—uneven, unstable, brightly coloured surfaces—that reflect the conditions beneath them. The exhibition trusts the viewer to make connections, to feel discomfort, to resist the urge to tidy things up mentally. It insists that art does not have to explain itself fully to be honest.

In the end, PAPER CUT feels less like an installation and more like an interruption. A reminder that before art became something to defend, monetize, or posture through, it was something done with whatever was at hand. Crayons. Glue. Time. Curiosity. And maybe, buried under layers of strategy and self-awareness, that impulse is still there—waiting for permission to be messy again.

No comments yet.