In the pantheon of American cinema, certain films dare not to embellish or dramatize reality—but to reflect it with such rawness that it becomes nearly unbearable to watch. Jerry Schatzberg’s 1971 feature, Panic in Needle Park, is one such film. It doesn’t merely document addiction—it lives inside it, moving with the same chaotic rhythm, the same blurred temporality, the same hungry desperation as its characters. More than fifty years later, the film remains a masterpiece of empathic realism, one that broke conventions and introduced the world to Al Pacino’s combustible talent, while giving voice to an American underclass often left unseen.

The Geography of Desperation: Sherman Square as Narrative Ground

The film draws its title from Needle Park, a colloquial name for Sherman Square, a modest triangular traffic island on New York City’s Upper West Side. In the late 1960s and early ’70s, this space had become a notorious haunt for heroin users and dealers—a public nexus of private ruin. Rather than recreate the setting in controlled studio conditions, Schatzberg shot entirely on location, allowing the film’s urban canvas to feel as cracked and chaotic as the lives it housed.

This isn’t a romantic New York, nor even a noir one—it is apathetic and unflinching, full of noise, shadows, dirty snow, and the occasional dog-walker who passes indifferently by. It’s a city both indifferent and complicit, functioning as a third character in the tragic love story at the heart of the film.

Story of a Fix: Bobby and Helen

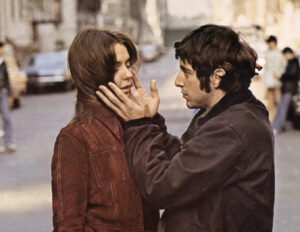

At its center, Panic in Needle Park is a love story—or, more accurately, a story of what happens when love isn’t enough. Al Pacino, in his first leading film role, plays Bobby, a young hustler and heroin addict who drifts through the city with manic energy and streetwise charm. His co-star, Kitty Winn—who won Best Actress at Cannes for this performance—is Helen, a young woman fresh from a failed abortion, quickly drawn into Bobby’s orbit.

Their chemistry is undeniable, magnetic in its early tenderness. But this is not a story of healing; it is one of slow co-destruction. As Helen slips into heroin use and eventual dependency, Bobby oscillates between caretaker, enabler, and victim. The two become one another’s only point of gravity, locked in a cycle where love becomes indistinguishable from compulsion.

Theirs is not the Hollywood depiction of addiction. There are no climactic interventions, no noble recoveries, no sudden acts of redemption. There is simply survival—barely—and the brutal recognition that addiction hollows out even the purest intentions.

Al Pacino: A Debut That Defines

Before The Godfather, before Serpico, Pacino was Bobby—an edgy, impulsive live wire whose every glance and shrug contains both seduction and self-sabotage. Watching his performance today is to witness the arrival of a major talent in its most unguarded form.

Pacino’s Bobby is not a villain, nor a romantic antihero, but a composite of contradictions: tender yet manipulative, magnetic yet aimless. He is generous one moment, cruel the next. In one scene, he steals for Helen; in another, he berates her for stealing herself. Pacino resists the urge to make Bobby likable, instead presenting him as a human being collapsing under the weight of his own appetites.

It’s a performance that feels eerily contemporary—more akin to the emotional realism of indie cinema than the stylized method acting of his generation. Pacino doesn’t ask for our sympathy. He earns it by not demanding it.

Kitty Winn: A Haunting Descent

While Pacino garners much of the film’s posthumous acclaim, Kitty Winn’s portrayal of Helen is the heart of the film’s ache. She enters the story as a lost woman, already wounded but not yet broken. As she falls into addiction, Winn traces Helen’s transformation with such quiet devastation that it’s easy to miss just how calculated and layered her choices are.

She doesn’t overplay the withdrawal scenes. She doesn’t cry through every betrayal. Instead, she gives us a slow withering, as though Helen is trying to protect some final untouched part of herself, even as it erodes.

In Helen, we see the mirror of Bobby’s descent—but also something arguably more tragic: the descent of someone who wasn’t supposed to fall. She is the viewer’s entry point into the world of Needle Park—and by the time she becomes indistinguishable from it, we feel complicit.

Cinematic Austerity as Moral Clarity

Director Jerry Schatzberg, a former fashion photographer, brings a documentarian’s sensibility to Panic in Needle Park. The camera lingers, hand-held and intimate, rarely breaking from realism. There is no soundtrack to guide our emotions, no stylized score to romanticize the pain. Instead, scenes play out in near silence, broken only by the ambient sounds of the city: traffic, footsteps, distant shouting.

This lack of manipulation forces the viewer into the uncomfortable position of witness, not spectator. The drug use is depicted graphically—needles go into skin, veins are missed, blood is drawn—not for shock, but for truth. The camera does not flinch, and neither can we.

Thematic Echoes: Love, Addiction, and the Failure of Institutions

The film’s most enduring theme is the limits of love in the face of dependency. Bobby and Helen love each other, perhaps even profoundly—but that love is infected by the illness they share. In Panic in Needle Park, love is not salvation. It is another tether, another needle.

Also powerful is the film’s critique of institutional indifference. There are no social workers, no helpful policemen, no rehab centers offering guidance. The city itself becomes the antagonist, swallowing its most vulnerable in bureaucratic silence. It’s a sobering reminder of how systems fail—not in dramatic ways, but through simple neglect.

Cultural Legacy and Influence

At the time of its release, Panic in Needle Park was radical. Films about drug use existed, but none with this level of candor or intimacy. It influenced everything from Requiem for a Dream to Trainspotting, embedding itself into the DNA of future addiction cinema.

Yet what makes the film most timeless is its refusal to moralize. There are no heroes. No villains. Just two people, locked in a tragedy of circumstance and choice.

Its visual and emotional restraint marked a shift in American cinema—toward the personal, the political, and the unpretty. The film’s gritty style would come to define the New Hollywood movement, while its themes remain urgently relevant today, in an era of opioid epidemics, mental health crises, and still-unresolved questions about the line between survival and surrender.

A Masterwork in Quiet Devastation

Panic in Needle Park is not a film that pleads for attention. It doesn’t stylize pain or aestheticize suffering. Instead, it documents it with journalistic precision and artistic empathy, making it all the more devastating.

It is a love story with no resolution, a cautionary tale with no villain, a portrait of addiction that refuses both redemption and spectacle. And in that restraint, it becomes one of the most honest films about urban despair ever made.

Over five decades since its release, Schatzberg’s masterpiece remains painfully contemporary. We still live in a society where love is not enough, where institutions look away, where addiction ruins lives slowly and without ceremony.

No comments yet.