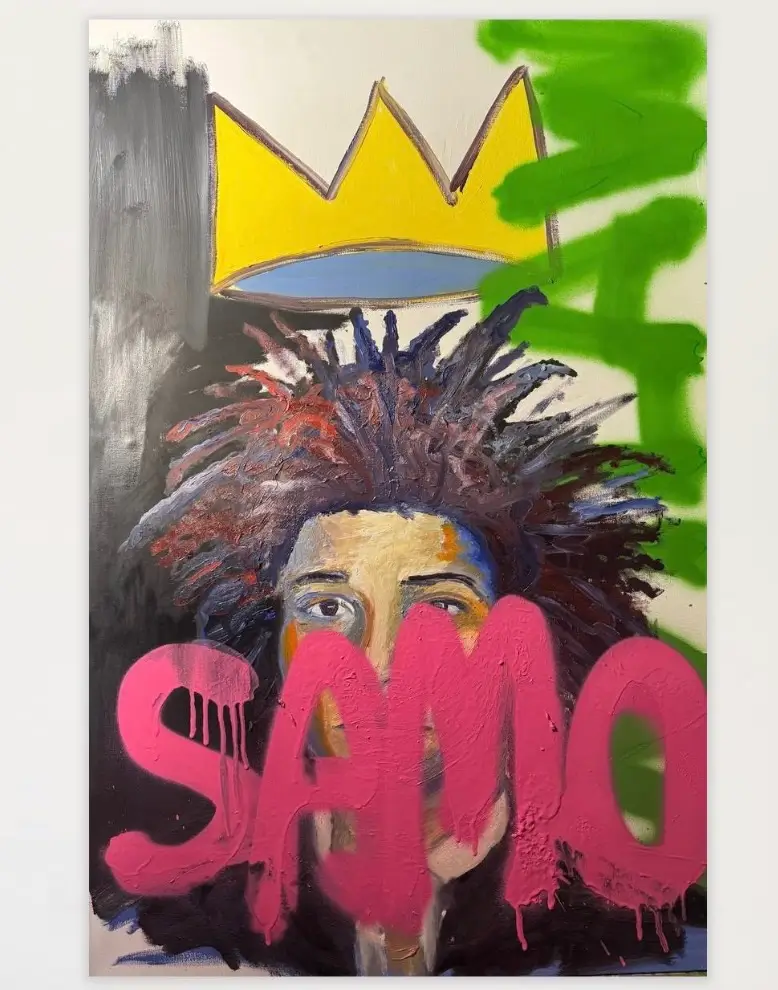

Few marks in late twentieth-century art carry the cultural voltage of SAMO. Originally scrawled across the walls of Lower Manhattan by Jean-Michel Basquiat and Al Diaz in the late 1970s, the phrase—short for “Same Old Shit”—operated as both a critique and a cipher. It was a street-level manifesto, ironic and confrontational, aimed at systems of belief, power, and complacency. Long after Basquiat’s meteoric rise and premature death, SAMO has remained a conceptual residue rather than a closed chapter. It is less a historical artifact than an open question.

Bash Wathier’s SAMO (Basquiat Tribute) enters this unresolved space. Created in the United States and executed in oil on canvas, the painting does not attempt imitation or stylistic ventriloquism. Instead, it positions itself as an act of dialogue—between generations, between street and studio, and between the mythologized figure of Basquiat and the contemporary artist navigating his shadow. Wathier’s work asks what it means to invoke SAMO now, in a moment when Basquiat has become both canonized and commodified.

trib

Tribute in contemporary art is a fraught proposition. To reference Basquiat is to risk comparison with one of the most over-reproduced visual languages in modern painting. Crowns, skeletal figures, frenetic linework, and text fragments have been endlessly appropriated, often stripped of their urgency. Wathier avoids this trap by refusing direct quotation. His SAMO (Basquiat Tribute) is not a pastiche of Basquiat’s marks but a meditation on what those marks once disrupted.

The painting operates through restraint rather than excess. Where Basquiat often crowded the canvas with symbols and words that collided and contradicted one another, Wathier allows space, tension, and silence to perform much of the work. The invocation of SAMO is conceptual rather than literal; it hovers as an idea rather than asserting itself as graffiti-style text. This approach acknowledges that SAMO’s original power lay not in its graphic form alone, but in its refusal to behave like art.

flow

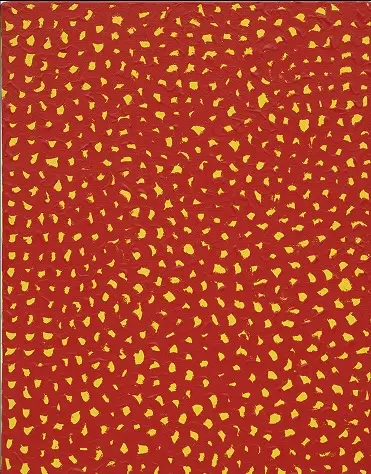

The choice of oil on canvas is not incidental. Basquiat himself famously transitioned from street surfaces and found materials to canvas as he entered the gallery system, a shift that mirrored his rapid absorption into the art market. Wathier’s use of oil engages directly with this lineage. Oil paint carries with it centuries of art-historical authority, from Renaissance portraiture to Abstract Expressionism. To deploy it in a work referencing SAMO is to stage a confrontation between institutional tradition and anti-institutional gesture.

Wathier’s handling of oil is controlled but expressive. The paint does not behave decoratively; it resists polish. Surfaces appear worked, revised, and partially unresolved, suggesting a process that values hesitation as much as assertion. In this way, the medium becomes a site of tension rather than a vessel for mastery. The painting acknowledges its own material seriousness while questioning the structures that confer legitimacy on that seriousness.

myth

Basquiat’s legacy today exists in multiple, often conflicting registers. He is simultaneously remembered as a radical outsider, a prodigious talent, and a market phenomenon whose works command astronomical prices. This saturation risks flattening the complexity of his practice into a series of recognizable tropes. Wathier’s tribute engages with what might be called the “Basquiat afterimage”—the lingering imprint of his work on contemporary visual culture.

Rather than reanimating Basquiat’s imagery, Wathier addresses the conditions that made SAMO possible. The painting gestures toward a time when critique could be raw, anonymous, and resistant to capture. In doing so, it implicitly asks whether such a position is still viable. Can an artist today invoke SAMO without turning it into a brand? Can dissent survive translation into oil and canvas?

concept

In Wathier’s painting, SAMO functions less as a reference to a specific historical act and more as a conceptual framework. It stands for skepticism toward authority, suspicion of art-world orthodoxies, and the refusal of easy meaning. This reframing allows the work to exist as an independent statement rather than a derivative homage.

The absence of overt iconography associated with Basquiat—crowns, skulls, anatomical drawings—creates a productive distance. Viewers familiar with Basquiat may sense the reference without being guided by visual shorthand. This subtlety respects the intelligence of the audience while preserving the painting’s autonomy. SAMO becomes a lens through which the work can be read, not a label that dictates interpretation.

influ

One of the most compelling aspects of SAMO (Basquiat Tribute) is its ethical stance on influence. Contemporary art is saturated with citation, remix, and revival. Wathier’s painting suggests that influence need not be visual to be substantive. By engaging with Basquiat at the level of attitude rather than appearance, the work models a more responsible form of homage.

This approach aligns with a broader shift in contemporary painting, where artists increasingly interrogate the systems they inherit rather than simply reproducing their aesthetics. Wathier acknowledges Basquiat not as a style to be borrowed, but as a precedent for critical independence. In doing so, the painting resists the nostalgia that often accompanies tributes and instead insists on relevance.

mat

Despite its conceptual rigor, the painting does not read as purely cerebral. There is an emotional register that emerges through color, texture, and composition. The surface carries a sense of abrasion and vulnerability, as though the painting itself is negotiating its position between reverence and resistance. This emotional complexity echoes Basquiat’s own work, which often oscillated between bravado and fragility.

Wathier’s restraint amplifies this effect. Rather than overwhelming the viewer, the painting invites prolonged looking. Subtle shifts in tone and texture reward attention, reinforcing the idea that meaning is not immediately available. This slowness feels intentional, a counterpoint to the rapid consumption of Basquiat imagery in popular culture.

medium

Created in the United States, SAMO (Basquiat Tribute) is inescapably situated within an American context. Basquiat’s work was deeply entangled with questions of race, class, and power in late twentieth-century America. While Wathier does not explicitly restage these themes, the invocation of SAMO carries their residue.

The painting reflects a contemporary American art landscape in which dissent is often aestheticized and absorbed by institutions. By choosing oil on canvas—a medium still closely associated with gallery and museum validation—Wathier foregrounds this contradiction. The work does not resolve the tension between critique and complicity; it stages it.

show

One of the enduring questions raised by Basquiat’s career is what happens when street energy enters the white cube. Wathier’s painting revisits this question from a temporal distance. The street is no longer the primary site of resistance it once was; digital platforms, social media, and virtual spaces now play that role. Yet painting persists as a medium capable of slow, embodied reflection.

SAMO (Basquiat Tribute) suggests that painting can still function as a site of critique, not through immediacy but through durability. Oil on canvas demands time—time to make, time to view, time to historicize. In this sense, the work reframes resistance not as speed, but as persistence.

fwd

What ultimately distinguishes Wathier’s painting is its refusal to be consumed solely as a Basquiat reference. While the tribute is explicit in the title, the painting insists on being encountered on its own terms. This balance between homage and autonomy is difficult to achieve, particularly when engaging with an artist as culturally dominant as Basquiat.

Wathier accomplishes this by allowing SAMO to remain unresolved. The painting does not explain itself, nor does it attempt to summarize Basquiat’s legacy. Instead, it occupies a space of questioning—about influence, authenticity, and the conditions under which art retains its critical force.

sum

SAMO (Basquiat Tribute) by Bash Wathier does not seek to resurrect Basquiat or replicate his visual language. It acknowledges that Basquiat’s most radical gesture was not a style, but a stance. By engaging with SAMO as an idea rather than an image, Wathier positions his painting within a lineage of critical inquiry rather than aesthetic mimicry.

In an art world that often rewards familiarity, this restraint is significant. The painting affirms that Basquiat’s legacy is not exhausted, but neither is it available for casual reuse. SAMO, in Wathier’s hands, becomes less a slogan than a provocation—one that continues to challenge artists to ask uncomfortable questions about value, power, and the meaning of resistance.

Forty-plus years after SAMO first appeared on New York walls, its spirit remains unsettled. Wathier’s painting does not claim to resolve that unrest. Instead, it honors it—quietly, deliberately, and with a seriousness that acknowledges both the weight of history and the necessity of moving forward.

No comments yet.