a digital tribute done right

When Hyundai unveiled the Ioniq 5 in 2021, the automotive world paused for a moment. Here was a mainstream electric crossover that didn’t hide behind generic futurism. It had texture, character, and intent — a clear design language built on the interplay between sharp geometry and subtle nostalgia. The most distinctive element was its pixelated lighting, blocky LED clusters that framed both the front and rear with a digital glow. Those pixels instantly became Hyundai’s signature — the visual equivalent of a company finding its voice.

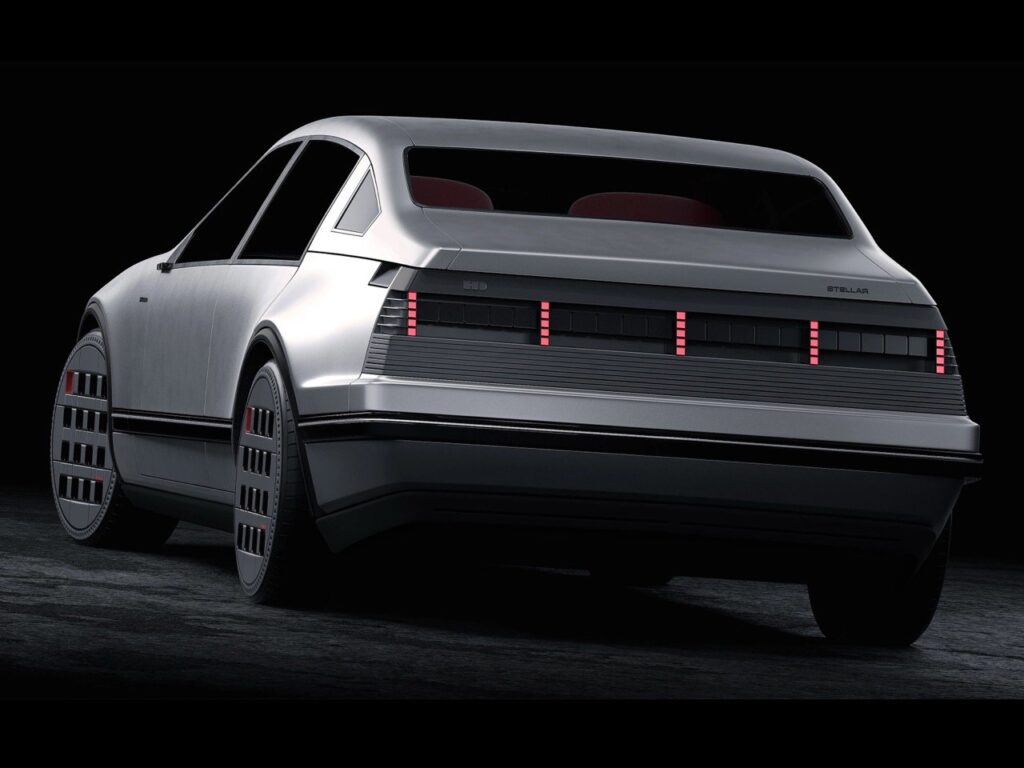

Fast-forward a few years, and the ripple effect of that discovery can be seen not only in Hyundai’s production line but also in the imagination of independent designers. That’s where the Second Star Project enters the scene — a fan-made concept by exterior designer Hyun Been Kye and interior designer Chris Min, hosted on Behance. Built in Blender and Mayaover just three weeks, this reinterpretation of the 1980s Hyundai Stellar demonstrates the creative potential of digital tools when guided by sharp conceptual clarity.

from forgotten sedan to cult inspiration

The original Hyundai Stellar was not an icon. Produced between 1983 and 1992, it was a modest rear-wheel-drive sedan designed by Giorgetto Giugiaro — competent but conservative. Outside Korea, it registered as little more than a curiosity. For most automakers, that level of anonymity would relegate it to history’s junk drawer. But for Kye and Min, that blankness was freedom.

By choosing a forgotten model, they sidestepped the burden of nostalgia. There were no brand loyalists to anger, no sacred styling cues to respect. This allowed them to reinvent rather than restore. The Second Star Project takes the Stellar’s basic wedge silhouette and recontextualizes it as a retro-futurist object — something that could exist in a parallel universe where the analog 1980s evolved directly into the digital age.

Kye’s reimagined front fascia makes that intent immediately clear. The car’s “face” is now dominated by a full-width LED grid, a matrix of glowing rectangles that function simultaneously as headlamps, signal indicators, and visual signature. It’s a bold continuation of Hyundai’s pixel design DNA, but in a more experimental form. Instead of treating pixels as accents, Kye uses them as architecture — light as structure, not decoration.

pixel language as identity

What makes the Second Star Project compelling is how fluently it speaks Hyundai’s new visual language without falling into imitation. The Ioniq series has established a motif where illumination doubles as identity. In that lineage, Kye’s design feels like an evolution — an unrestrained experiment in pixel modularity.

The grid across the nose isn’t simply aesthetic. Conceptually, it frames the vehicle as a screen-based organism — a car designed for an era when interfaces define experience. The lighting pattern could, in theory, communicate status or emotion, blending the language of UI with the physical form of a vehicle.

From a design standpoint, this reinterpretation touches on something deeper: how digital culture influences automotive design. We no longer see cars as mechanical sculptures; we see them as interactive devices. The Second Star Projectdoesn’t shy away from that. Its blocky light clusters, deliberately reminiscent of 8-bit displays, evoke early computing and classic console graphics — nostalgia reimagined through a contemporary digital lens.

This is where the project transcends fan art. It’s not merely an aesthetic exercise but a commentary on how identity in design can be coded, pixel by pixel.

the role of digital craftsmanship

In a time when 3D modeling and AI rendering have blurred the line between concept and reality, Kye and Min’s process stands out for its discipline. Working within Blender and Maya, they approached the Second Star Project like a studio commission — exploring form, lighting, and proportion with professional precision.

Their workflow reflects the new democratization of design tools. Twenty years ago, producing something of this visual fidelity would have required access to industrial software and rendering farms. Now, designers can build and publish at a global standard from personal laptops. That accessibility is reshaping design culture itself. Behance, Instagram, and ArtStation have become virtual showrooms where independent creators test speculative ideas that often rival, and sometimes surpass, official manufacturer work.

The Second Star Project embodies this shift. Its renders have the polish of an OEM presentation — soft studio lighting, brushed aluminum finishes, minimal color palette — but they carry a distinct outsider’s energy. Free from marketing constraints, the design speaks purely to form and feeling.

View this post on Instagram

reimagining heritage without nostalgia

Automakers are obsessed with heritage. Every year brings another “reinterpretation” of a beloved model — retro rebirths that play safe, evoking familiarity rather than vision. What makes Kye and Min’s approach so refreshing is their rejection of nostalgia as aesthetic crutch.

Their Stellar is not a revival; it’s a remix. They reference the original’s wedge stance and linear surfaces but filter it through a near-scientific lens. The result feels more like speculative fiction than restoration — as if the Stellar had been designed for a Tron sequel or as an AI vehicle in a Blade Runner-esque metropolis.

This blending of past and future — analog proportion, digital surface — produces what could be called temporal design, a style that collapses decades into a single object. It’s an aesthetic increasingly visible across creative industries, from watchmaking to fashion: the yearning for tactile form expressed through digital precision.

Kye’s vision situates Hyundai within that narrative, even if unofficially. It suggests that the company’s pixel aesthetic could evolve into something grander — not just a lighting motif, but a design philosophy about modularity, communication, and technological empathy.

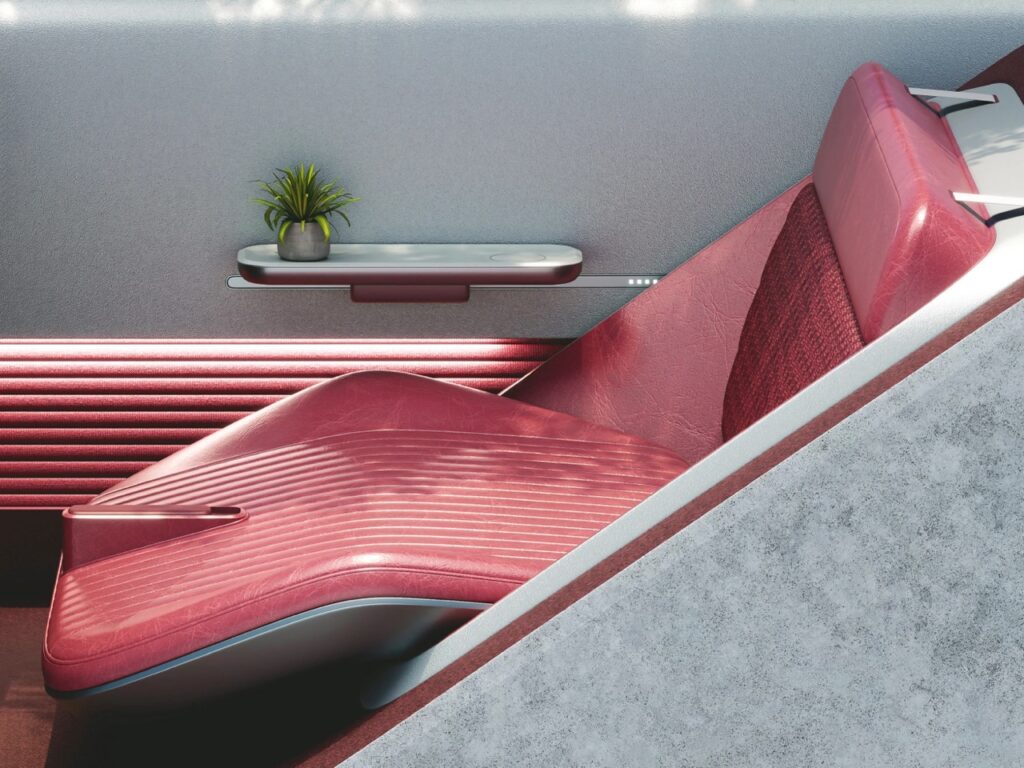

the interior: minimalism meets imagination

While Kye handled the exterior, Chris Min directed the cabin design, and his interpretation continues the dialogue between retro simplicity and digital modernism. The interior appears suspended in time — a minimalist volume defined by light bands, flattened surfaces, and an absence of visible controls.

What’s remarkable is how Min avoids the cliché of the “screen everywhere” future. Instead, he imagines a space where technology recedes into texture. Light and shadow perform the function of interface — a subtle nod to Hyundai’s own move toward “shy tech”, where interactive features remain invisible until needed.

The cabin’s tone feels contemplative, less about driving and more about inhabiting. There’s a sense of emotional neutrality — soft ambient hues, brushed metallic trims, and tactile surfaces that suggest both analog craftsmanship and synthetic intelligence.

It’s a poetic balance: digital restraint, analog soul.

digital nostalgia as modern design

The emotional undercurrent of the Second Star Project lies in its digital nostalgia — the way it treats pixels as both aesthetic and metaphor. The pixel, after all, is the most basic unit of digital imagery, the building block of all visual interfaces. To use it as a design motif for a physical object is to literalize the intersection between real and virtual worlds.

In this way, Kye’s and Min’s concept sits comfortably alongside contemporary design movements in fashion and architecture that celebrate imperfection and geometry — the “low-res aesthetic” of early computing translated into high-definition reality. The same creative impulse that drives artists like Daniel Arsham or studios like Sabukaru Design informs this concept: nostalgia as design material.

For Hyundai, even unofficially, that’s a gift. It proves the staying power of their design direction. When independent designers adopt your visual grammar, it means your brand has achieved something rare — cultural traction.

the influence of hyundai’s pixel era

It’s easy to forget how rapidly Hyundai has evolved as a design powerhouse. A decade ago, the brand was still finding its footing between affordability and aspiration. The Ioniq 5 changed that. Its angular geometry and pixelated detailing bridged futuristic minimalism with approachable warmth. It wasn’t just a car; it was a manifesto.

The ripple continued through the Ioniq 6 and the N Vision 74 — the latter explicitly mining 1970s and 80s heritage through a futuristic lens. But while those projects were official, the Second Star Project feels like their spiritual counterpart — a fan echo that validates Hyundai’s trajectory.

What’s particularly fascinating is that Kye’s concept could easily exist within Hyundai’s current portfolio. Its aesthetic consistency — the blend of rectilinear lighting, sculpted simplicity, and subdued palette — fits perfectly within the “Parametric Pixel” framework that has become Hyundai’s signature.

If anything, it suggests the potential for Hyundai to embrace fan concepts as creative collaborations. In an age where digital artists build convincing renderings indistinguishable from official releases, the boundary between enthusiast and professional design is dissolving.

the digital era

Projects like this force an uncomfortable but necessary question: what defines “authentic” automotive design in a digital world? If an independent designer can produce visuals as polished and conceptually rich as corporate studios, does authorship still matter?

The Second Star Project sits at that intersection. It’s unofficial yet deeply aligned with Hyundai’s ethos. It’s speculative yet grounded in functional realism. That duality — between fantasy and feasibility — is what gives it credibility.

More importantly, it points toward the future of automotive design culture: decentralized, open, and participatory.Brands no longer own the visual conversation around their identity; fans and freelancers do. When design languages are strong enough, they evolve beyond control — becoming frameworks anyone can build upon.

Kye and Min’s work isn’t an imitation; it’s a continuation.

why it feels more “real” than real concepts

Many official heritage concepts suffer from overproduction — slick surfaces masking conceptual emptiness. The Second Star Project, conversely, feels grounded because it’s driven by pure idea, not marketing narrative.

It doesn’t need to promise electrification, mobility services, or brand storytelling. It just asks: what if we built the past from the future? That question alone gives it emotional weight.

The restraint of the design — no exaggerated wings, no chrome theatrics — allows its pixel vocabulary to breathe. Each surface feels intentional, every line considered. The subtlety evokes confidence. That’s what gives the project its OEM-level credibility.

It’s a reminder that sometimes, the best design doesn’t come from committees, but from concentrated vision — two designers, three weeks, and a clear sense of purpose.

blending software and soul

What makes the Second Star Project especially resonant is its ability to merge technical craft with emotional storytelling. The designers aren’t just rendering surfaces; they’re translating feelings — the longing for clarity in an overstimulated visual world, the rediscovery of minimalism through technology.

Their use of light, in particular, blurs function and poetry. The pixel grid doesn’t just illuminate; it communicates. It becomes a language between object and observer. That synthesis — emotional intelligence through digital means — is the future of automotive expression.

It’s also a reflection of generational aesthetics. Designers like Kye and Min grew up surrounded by screens. Their visual literacy was shaped by gaming consoles, computer GUIs, and lo-fi web graphics. To them, pixels are not limitations but symbols — shorthand for memory and possibility.

speculative design as critique

At its core, the Second Star Project is not fan service but speculative critique. It challenges traditional automotive timelines by suggesting that progress isn’t linear. Maybe the 1980s, with their geometric clarity, offered design lessons we’ve only just learned to appreciate.

By reconstructing the Stellar through digital precision, the project proposes an alternate evolution for Hyundai — one where early computing aesthetics, not aerodynamic homogeny, became the foundation of design identity.

This speculative framing transforms nostalgia into narrative. It doesn’t ask us to remember the past but to imagine what could have been if design had followed a different code.

No comments yet.