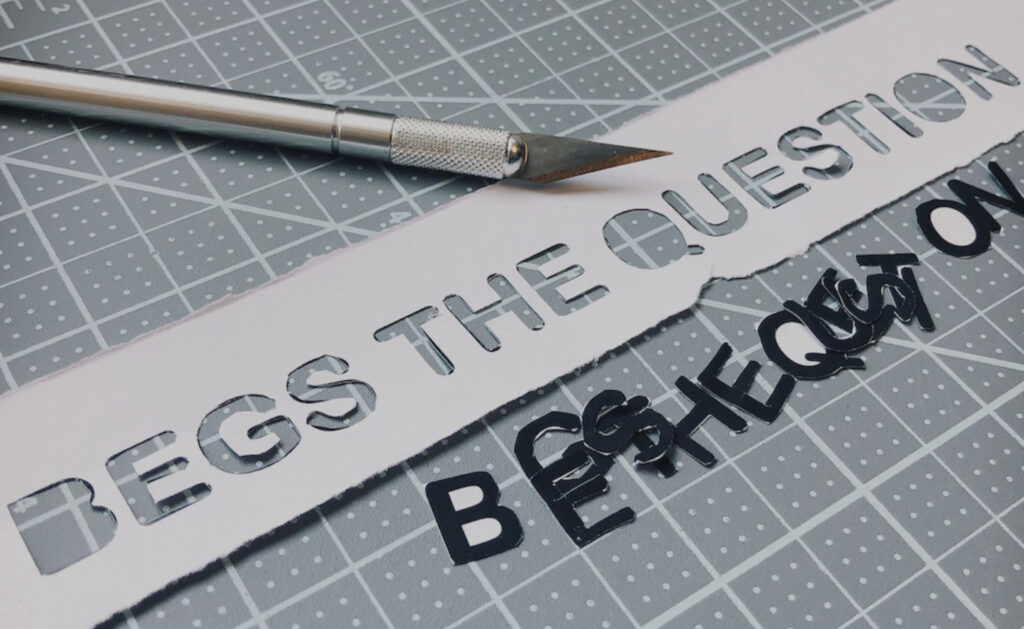

A Rhetorical Reckoning in Modern Usage

In the great, sprawling landscape of the English language, few phrases have lived two lives as distinctly—and divisively—as “begs the question.” For grammarians and philosophers, the phrase conjures the logical fallacy petitio principii, wherein an argument’s premise assumes the truth of the very thing it seeks to prove. Yet in mainstream usage, “begs the question” has taken on an entirely different identity: it now commonly stands in for “raises the question,” especially in journalism, advertising, and casual speech.

This semantic rift has fueled decades of linguistic debate, prompting purists to lament the loss of precision and pragmatists to shrug off the change as natural evolution. As we stand at the crossroads of prescriptive rigor and descriptive reality, one wonders—should English speakers finally retire the phrase “begs the question” altogether?

The Philosophical Roots: A Logical Legacy Misunderstood

To understand the storm of controversy, one must first trace “begs the question” back to its roots in classical rhetoric. The phrase stems from the Latin petitio principii, which literally translates to “assuming the initial point.” In logic, this fallacy occurs when an argument’s conclusion is smuggled into its premise, rendering the reasoning circular. For instance, stating “We must trust him because he is trustworthy” presumes the very trait it aims to establish.

This logical flaw was once central to the study of reasoning and debate, particularly in Western philosophical traditions. Aristotle identified it as a fundamental error, one that could render entire arguments meaningless. For centuries, “begs the question” was a specialized term of art in philosophical and academic contexts, cherished for its precision.

But therein lies the irony: the very specificity that made “begs the question” valuable also made it vulnerable to misinterpretation. As the phrase left the cloistered halls of philosophy and entered broader English usage, its meaning shifted—some would say drifted—toward a more intuitive, less pedantic interpretation.

The Modern Misuse: Raising More than Eyebrows

Today, it is far more common to hear “begs the question” used in place of “raises the question.” A journalist might write, “The sudden drop in polling numbers begs the question: is the candidate losing support?” or a marketing analyst might declare, “The success of the campaign begs the question of what comes next.” In both cases, the speaker clearly means that one idea leads logically to another question—not that a logical fallacy has been committed.

To defenders of traditional usage, this is linguistic heresy. They argue that the misuse not only dilutes the precision of an important philosophical concept but also propagates misunderstanding about what constitutes sound reasoning. Precision in language, they contend, is not mere pedantry—it’s intellectual hygiene. Just as misusing the word “literally” can sow confusion (“I literally died laughing”), so too does misusing “begs the question” blur the boundaries of logic.

And yet, to the average English speaker, the traditional usage of “begs the question” is arcane at best and alien at worst. According to linguistic surveys, fewer than 20% of English speakers can correctly identify the original meaning of the phrase. In contrast, the “raises the question” interpretation is immediately accessible and intuitively clear. If the goal of language is communication, is it fair—or even useful—to preserve a meaning that most people no longer recognize?

Linguistic Flow and the Case for Descriptivism

Language, like culture, is not static. It evolves with its speakers, adapting to new contexts, needs, and patterns of understanding. What was once a sacred cow can become a linguistic relic. Descriptivists—those who describe language as it is used rather than prescribe how it ought to be used—see the transformation of “begs the question” not as a degradation but as a natural linguistic progression.

In this light, the shift in meaning is neither catastrophic nor surprising. Similar changes have occurred throughout English history. “Decimate” once meant to kill one in every ten; now it simply means to destroy. “Awful” once meant awe-inspiring; now it means terrible. “Nonplussed” has drifted so far from its original meaning (confused) that many now use it to mean unfazed. Language is full of such reversals, reinterpretations, and reinventions.

From this perspective, insisting on the original meaning of “begs the question” is like trying to hold back a tide with a broom. If a phrase no longer serves its intended purpose—and actively causes confusion in most of its real-world applications—then perhaps it is time to let it go.

A Compromise: Clarity Through Recalibration

Yet total abandonment may feel like surrendering to chaos. For educators, logicians, and thinkers who still rely on the original meaning of “begs the question,” the loss of that phrase represents a diminishment of intellectual tools. So is there a middle ground?

One solution is to recalibrate our vocabulary. Rather than insisting on “begs the question” to describe circular reasoning, writers and educators could prefer the direct and unambiguous phrase “circular logic” or “assumes the conclusion.” These expressions convey the same idea with greater clarity and less potential for confusion. Meanwhile, those who simply mean “raises the question” should feel free to use exactly that—without resorting to a phrase that may muddle the point.

This approach respects both clarity and history. It preserves the logical concept while recognizing that the phrase attached to it has lost its mooring in public discourse. It also invites speakers to be more intentional with their language—choosing the most accurate expression rather than relying on rhetorical shorthand.

Impression

So, should English speakers retire “begs the question”? The answer depends on one’s view of language itself. If you believe language should preserve precision and guard its technical terms, then yes, the phrase is too far gone and better replaced with clearer alternatives. If, on the other hand, you view language as a living, breathing organism shaped by popular usage, then perhaps “begs the question” is simply being reborn as something new—no more correct or incorrect than any other idiomatic expression.

What is clear, however, is that the phrase now inhabits a gray area, neither universally understood nor consistently applied. Whether we retire it, revise it, or reclaim it, the real call is for mindfulness: to use language not just out of habit, but with an eye toward clarity, purpose, and shared understanding. In the end, that’s what language is for—not to win arguments, but to ensure they happen meaningfully.

No comments yet.