A Time Capsule Beneath the Streets

In today’s world of contactless payments, GPS-enabled route planning, and clean transit campaigns, it’s easy to forget that just five decades ago, New York City’s subway system teetered on the edge of collapse. In the 1970s, the subway was far more than a method of transportation—it was a mirror held up to the city’s rawest edges. It showcased New York’s resilience, its turmoil, its diversity, and most memorably, its contradictions.

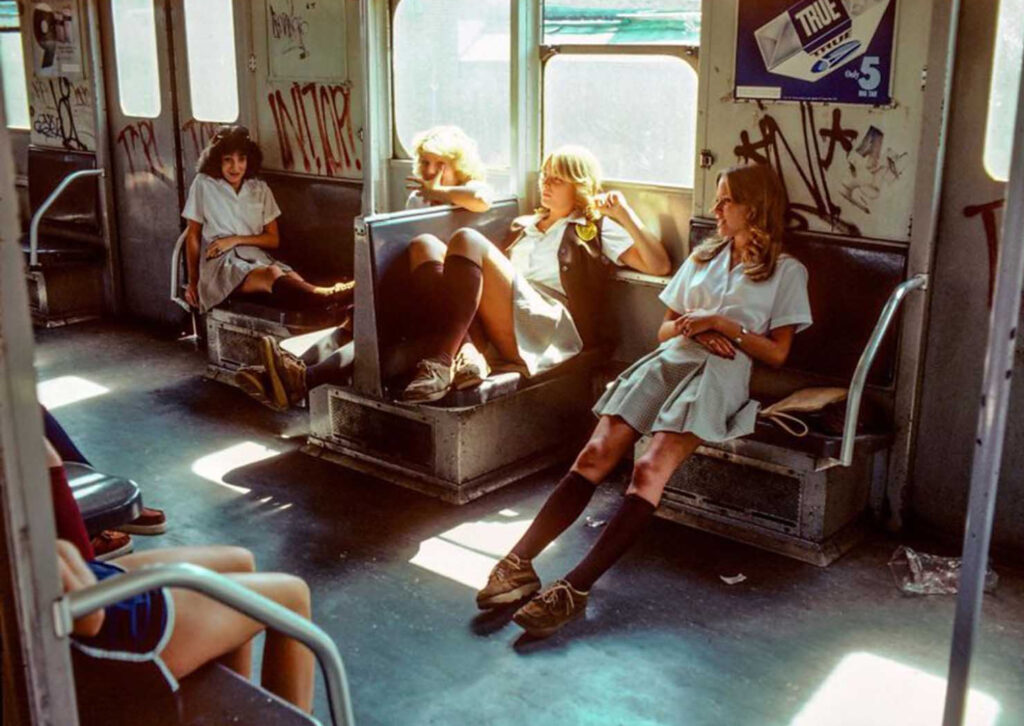

The gritty documentation by photographers like Joni Sternbach, who turned her lens on the worn seats and weary faces of subway riders, helps us not only remember but feel the human complexity of that time. Sternbach’s work was not voyeuristic, but participatory—part love letter, part elegy. Each frame captured in the murky underground was a tribute to survival.

Today’s reflection on the subway system of the 1970s is not a nostalgic act of romanticizing urban decay. It is a reckoning with how far we’ve come—and how close we may still be to some of the same systemic struggles.

The Crisis Underground: Subway in Decline

The New York subway system in the 1970s was plagued by mechanical failure, financial disrepair, and public distrust. Amid the broader economic crises that struck the city—culminating in the infamous 1975 near-bankruptcy—the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) found itself drowning in deferred maintenance, rising crime, and plummeting morale.

Trains broke down frequently, stations were dimly lit and grimy, and graffiti—seen by some as art and by others as vandalism—covered nearly every surface. The term “ghost trains” became shorthand for cars so derelict that they seemed like relics from a city that had lost hope.

Yet for all its failures, the subway remained essential. Over three million people used the system daily—many of whom had no alternative. Immigrants, working-class New Yorkers, artists, hustlers, and Wall Street suits all shared the same cars.

The Rise of Subway Graffiti: Canvas of a City’s Anguish

The 1970s subway wasn’t just a vehicle—it was a gallery, a bulletin board, a cry for attention. The rise of graffiti culture is inseparable from the era’s transit story. Emerging primarily from Black and Latino youth communities in the Bronx and Brooklyn, artists like Taki 183, Lee Quiñones, Dondi White, and Lady Pink transformed subway cars into moving murals.

Graffiti was a means of cultural ownership in a city that routinely erased marginalized voices. Every tag and burner was a protest against invisibility. Joni Sternbach’s images, while not focused solely on the graffiti itself, nevertheless captured its looming presence—an ambient force in every ride, echoing youth rebellion, aesthetic experimentation, and resistance.

Mainstream media, city officials, and the MTA declared war on graffiti, associating it with crime and moral decay. Yet from today’s vantage point, many of those same works are recognized as seminal contributions to global street art.

The Human Landscape: Riders in Transit

Sternbach’s photography focused on riders—not trains. Her images weren’t about the infrastructure, but about people inside it: a sleeping construction worker; a sharply dressed woman clutching her handbag; a group of kids sharing candy in a graffiti-soaked car.

What makes these photos particularly resonant today is how intimate and unaffected they are. There’s no curated fashion, no performance for the lens—just raw moments of vulnerability, fatigue, contemplation, and camaraderie.

In an age of social media aesthetics and algorithm-driven visibility, Sternbach’s photos remind us of a pre-curated world. Her work offers a democratic, even poetic, look at New York’s pulse.

The R46: Hope on Steel Wheels

In 1975, a beacon of hope arrived in the form of the R46 subway car. Manufactured by Pullman Standard, the R46s were heralded as the next chapter in NYC transit: they were wider, brighter, quieter, and fitted with advanced features like air suspension and energy-efficient motors.

But the R46 rollout was bumpy. Structural cracks, braking failures, and door malfunctions plagued the fleet. Still, the arrival of these modern cars symbolized the city’s determination to rebuild and reimagine its public services, even in the face of staggering odds.

Today, though much refurbished, many R46 cars are still in use—a testament to their durability and symbolic weight. They represent the beginning of the long road toward modernization.

Echoes in the Present: What We’ve Inherited

Fast-forward to 2025. The MTA is again caught in a fiscal web, struggling with post-pandemic ridership, climate resilience, and the equitable rollout of technology. Surveillance has replaced graffiti, and art installations are now formally commissioned by the MTA Arts & Design program.

The platform conversations have shifted—from fears of muggings to debates over fares, facial recognition, and infrastructure equity. However, the essence remains the same: the subway is still where New York is most itself.

Today’s social movements—Black Lives Matter, labor strikes, climate protests—still course through these same tunnels. Performers still spin on poles, and preachers still proselytize. In that way, the subway remains a stage, a shelter, a battleground, and a sanctuary.

Urban Memory and Transit Trauma

When we reflect on the 1970s subway, we are also reckoning with the trauma of urban neglect. The system’s decay was not just a failure of engineering—it was a symptom of social abandonment.

The modern MTA’s slow adoption of accessibility measures, its treatment of homeless riders, and its resistance to fare-free transit zones are reminders that while the hardware has changed, many of the underlying issues remain unresolved.

The 1970s subway legacy forces us to ask: How do cities treat their most vulnerable? Are public services truly public when they operate as commercial enterprises? How do we democratize mobility?

Joni Sternbach’s Legacy: Seeing the Unseen

Joni Sternbach, best known today for her tintype seascapes and surf culture portraits, cut her teeth on these subway portraits. While her later work would return her to natural light and collodion plates, her early years spent in the backdrops of the subway gave her an enduring sensibility—attuned to contrast, patience, and silence.

Her images of New York’s underground aren’t just documentation. They are acts of witnessing. They remind us that beauty can be found in decay, that dignity survives even in neglect, and that every stranger is a story waiting to be told.

Impression: Lessons in Steel and Silence

Looking back, the 1970s subway is not just a relic or cautionary tale. It is a paradigm—a lived case study in how cities manage (or mismanage) growth, community, expression, and decline.

The graffiti-covered cars, the tired commuters, the R46’s first shakedown run—all of it underscores a fundamental truth: public transit is not just about movement, but meaning.

As New York once again reimagines its underground arteries in the age of climate change and AI, we would do well to remember that progress must be measured not only by speed and cleanliness but by human presence, cultural memory, and urban empathy.

Sternbach’s images, the R46’s creaks, the tags that once danced across steel—these are the echoes of a subway that never stopped running, even when the city above it nearly did.

No comments yet.