There are moments in modern game design when visual fidelity ceases to serve as mere background dressing and ascends into narrative poetry. In Star Wars Jedi: Survivor, developed by Respawn Entertainment, one such moment arrives through something deceptively subtle: the enigmatic, corrupted crystal formations known as Koboh Matter. These eerie tendrils, twisted and luminous, erupt from surfaces like alien obsidian arteries—alive with arcane menace and visual depth.

At the pithy of these spectral structures is Kevin Quinn, Lead Environment Artist at Respawn, whose innovative use of Houdini Engine scripting transformed Koboh Matter from concept into an interactive, procedural, and artist-driven ecosystem. In a galaxy of lightsabers and legends, it’s the environmental design that often goes unnoticed—but here, Koboh Matter doesn’t just decorate a level. It shapes how players move, what they feel, and how they perceive the dying beauty of the game’s planet Koboh.

Koboh as Environmental Metaphor

The planet Koboh functions not just as a terrain but as a character—haunted, fractured, caught between industrial exploitation and natural rebellion. Its dominant visual signature is Koboh Matter—a toxic, violet corruption threatening to overtake the biosphere. It resists passage, obstructs vision, and demands active removal using Force powers or strategic traversal.

Kevin Quinn’s role, working under art directors Nate Stephens and Chris Sutton, was to give that corruption form—dynamic, dimensional, and expressive. This wasn’t just about laying pre-baked assets into levels. It was about authoring a modular design language that felt procedurally alive, yet meticulously authored by artists.

Enter Houdini—Controlled Chaos

To generate the varied formations of Koboh Matter, Quinn leveraged Houdini Engine—a procedural 3D toolkit from SideFX used widely in VFX and now increasingly adopted in AAA games. In contrast to traditional modeling tools, Houdini allows for parametric workflows, meaning the artist sets rules rather than shapes.

Two bespoke Houdini tools were developed:

- Koboh Tendril Tool: A spline-based placement system enabling artists to “grow” individual crystal tentacles with variation in curvature, density, and form. The visual result is serpentine matter that mimics growth, decay, and tension.

- Koboh Bramble Tool: Designed to mass-deploy tangled matter clusters across surfaces and volumes. This was essential for dense infestations and also generated “burnable” variants—models dynamically erased when the player purges the area.

What makes these tools significant isn’t just their capability to generate content. It’s that they hand control back to the level artist. No longer shackled to static meshes or costly outsourcing pipelines, Quinn’s toolkit empowered designers to populate space with meaningful irregularity.

The Language of Tendrils

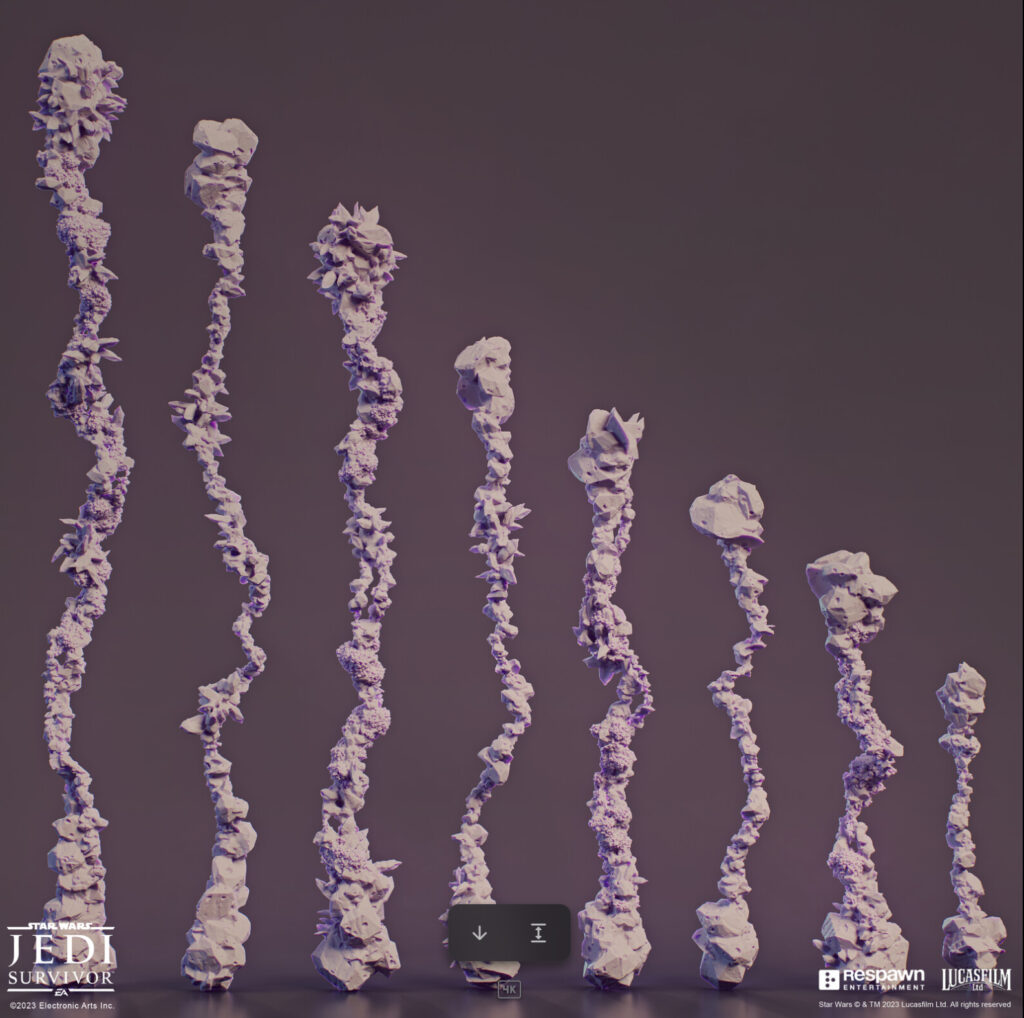

The visual grammar of the Koboh Tendrils—a set of vertical crystal chains seen prominently in concept art and level builds—demonstrates the team’s obsession with material storytelling. These formations aren’t uniform. Some spike with aggression. Others crumble mid-way. Some lean, fractured, or fold inward like organic scar tissue.

In the render attached above, we see nine unique tendrils arrayed in a lineup—a study in controlled asymmetry. The coloration is mauve-gray, subtle but iridescent. Under direct lighting, the formations glow faintly, as if pulsing with malignant energy.

This visual coding wasn’t random. It was tied to both narrative and gameplay. The shape of a tendril might imply whether it can be platformed over, avoided, or destroyed. Its density could influence collision detection. Its placement could guide or mislead the player. The design is elegant misdirection—guidance wrapped in grotesque beauty.

Technical Storytelling in Level Design

Koboh Matter served not just aesthetic goals but functional gameplay purposes. The brambles blocked off entire regions. Clearing them became both a reward and a rite of passage. The Houdini-generated variants allowed for dramatic pacing—some Koboh Matter patches could take the form of grand domes, others as creeper vines etched into architecture.

Quinn’s bramble tool allowed the game to scale complexity as players progressed. Early levels featured clean, sparse infestations. By mid-game, Koboh Matter dominated entire valleys, requiring players to use traversal techniques—wall running, double jumps, and new Force abilities—to purge the material.

What’s key is that this design wasn’t authored by a single artist hand-placing assets in Maya. It was authored through rules. Quinn’s Houdini tools let designers apply the logic of infection to the landscape.

Koboh Matter and Jedi Philosophy

This may sound esoteric, but it’s intentional: Koboh Matter, in its visual and interactive properties, echoes the internal conflict of Cal Kestis, the game’s protagonist. As he struggles between light and dark, trust and doubt, order and entropy, so too does the land beneath him fracture and bloom with otherworldly energy.

The design of Koboh Matter was a response to that thematic undercurrent. The tendrils and brambles are both antagonist and reflection—obstacles that externalize an inner dissonance. In purging them, the player enacts restoration. The metaphor lands because the art does.

Tools as Culture, Not Just Pipeline

Kevin Quinn’s development of these Houdini tools speaks to a broader shift in AAA pipeline culture. Increasingly, environment artists are expected to be toolmakers as well as designers—crafting systems that empower others rather than creating assets in isolation.

Quinn’s Tendril and Bramble tools are now part of Respawn’s internal suite, available to other teams and potentially applicable beyond Koboh. With tweakable parameters for height, twist rate, crystalline noise, and decay simulation, the tools act like biological generators—pumping out visual entropy with control sliders.

They save time. But more importantly, they seed creativity.

The Art Direction Touch

Under Art Directors Nate Stephens and Chris Sutton, the visual language of Koboh Matter matured into something cinematic. They insisted on avoiding anything that felt too “lava-like” or overtly alien. Instead, the goal was to reference mineralogical decay, bioluminescence, and even deep-sea coral.

It’s here that Quinn’s Houdini framework shined. Because the tools were live and responsive, changes to lookdev—whether to increase bloom intensity or modify spore density—could be made without scrapping the structure. The art direction was agile, reactive, and elevated.

Stephens described the process as “painting with infection.” And it shows.

Community Response and Recognition

When Jedi: Survivor launched, Koboh Matter became one of the most frequently discussed visual phenomena on forums and subreddits. Players screenshot it obsessively. Some tried to reverse-engineer its generation. Others likened it to formations from Annihilation or The Last of Us—but always with that Star Wars edge.

For game artists, it was a showcase of what procedural tools could offer when placed in the hands of visionaries.

At GDC 2024, Quinn’s pipeline was cited as a case study in “Scalable Detail Authored with Intent,” and SideFX named Respawn’s Koboh Matter among its top 10 Houdini game uses of the year.

Impression: Legacy in the Layers

In a medium defined by motion and mechanics, environmental art often sits at the periphery. But what Kevin Quinn and the team at Respawn achieved with Koboh Matter is nothing short of structural storytelling. They gave corruption a shape, infestation a personality, and resistance a visual arc.

And in doing so, they’ve left an imprint not just on Koboh, but on the future of procedural art in games—where every tendril tells a story, and every bramble remembers the hand that built it.

No comments yet.