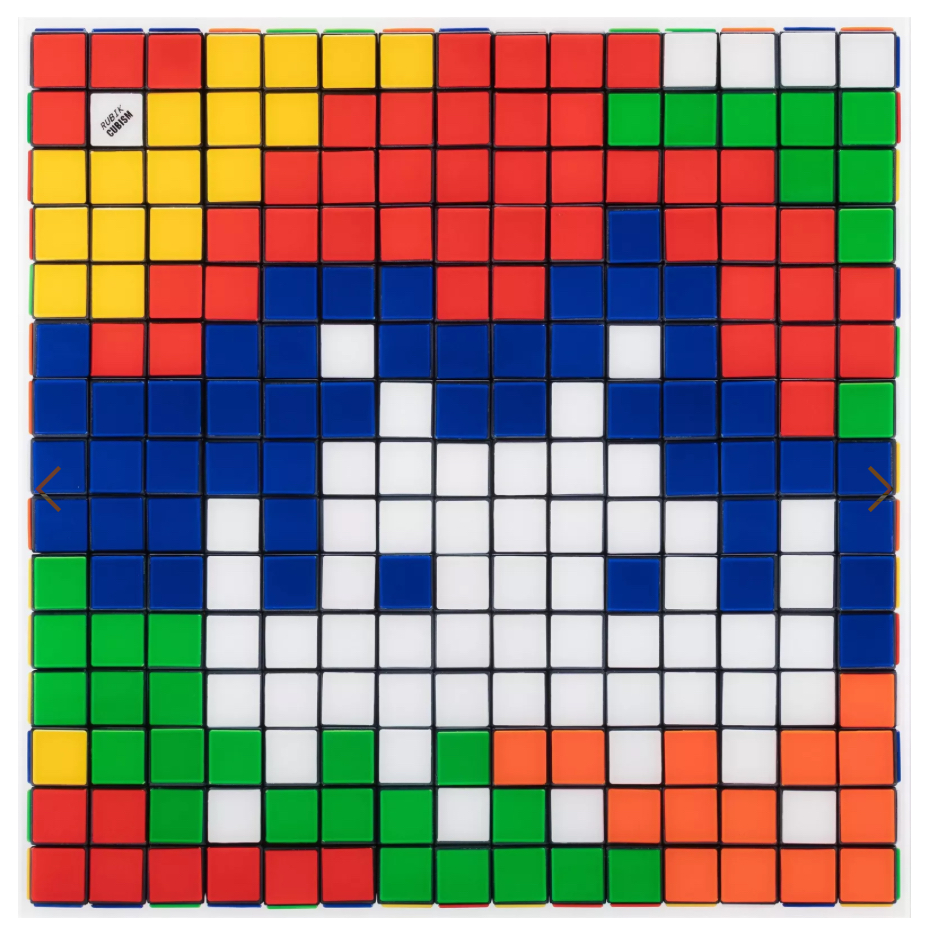

In the canon of contemporary urban interventionism, few figures stand out as starkly as Invader—the elusive French street artist whose Rubik’s Cube mosaics have colonized the world’s metropolises with cryptic elegance. Beneath his playful, pixelated veneer lies a deeper cartography of resistance, nostalgia, and socio-cultural critique. His 2023 work, Rubik Camouflage, rendered in giclée print on an aluminum composite panel, crystallizes these elements into a static-yet-fluid commentary on visibility, concealment, and the coded language of postmodern subversion. This piece is more than visual pastiche—it is conceptual insurgency disguised as play.

From Graffiti to Giclée: Translating the Urban into the Institutional

To understand Rubik Camouflage, one must first understand the artist’s ongoing project—Space Invaders—which began in 1998. With over 4,000 installations across more than 80 cities worldwide, Invader has built an unorthodox yet methodical empire of micro-interventions using ceramic tiles arranged into pixel-like characters inspired by 8-bit video games. These interventions sit between the sanctioned and the illicit, the nostalgic and the revolutionary. They are simultaneously ephemeral and archival, drawing on the tradition of graffiti but formalized in geometric abstraction.

Yet Rubik Camouflage marks a shift from street to studio, from found wall to framed panel. While the medium of giclée printing on aluminum reflects a museum-level elevation of street aesthetics, the subject—a pixelated abstraction using Rubik’s Cube color logic—is still steeped in a logic of decoding. This is a camouflage not for soldiers but for ideas; not to disappear in the forest, but to disappear in plain sight among capitalist gloss.

Chromatic Politics and the Rubik Method

Invader’s use of Rubik’s Cubes began in the mid-2000s, resulting in what he terms “Rubikcubism”—a method of composing imagery through the fixed palette of the iconic 3×3 puzzle. With only six colors to work with (white, yellow, red, blue, green, and orange), Rubik Camouflage leverages the constraints of the Rubik matrix to encode a message that defies immediate recognition. Like a cipher, the image is not legible until one decodes its pixel hierarchy.

But the camouflage motif adds another layer. Here, Invader draws upon military visual language—mimicry, disguise, and confusion—but applies it to the cultural landscape. What is being hidden? What is being protected? The viewer must ask: is this abstraction a disguise for a figure, an idea, a city? In a world where surveillance and visibility are entwined with identity and power, Rubik Camouflage posits the act of hiding as a form of resistance.

Post-Pop Disruption and Digital Archaeology

Despite its 8-bit roots, Rubik Camouflage is no simple tribute to vintage gaming. It occupies the complicated terrain of post-Pop disruption, echoing the color logic of Warhol, the repetition of Lichtenstein, and the obsessive indexing of On Kawara. But where Pop Art often reproduced commercial iconography to comment on mass production, Invader manipulates the language of early digital aesthetics to comment on mass information—specifically, how it is concealed, commodified, or resisted.

The notion of camouflage within the digital age evokes a deep sense of algorithmic invisibility: VPNs, encrypted channels, disappearing messages, and anonymized data structures. In this regard, Rubik Camouflage operates as a poetic artifact of digital archaeology, capturing the aesthetics of an earlier technological optimism while gesturing toward the veiled infrastructures of the contemporary surveillance state.

The City as Canvas, the Studio as Simulation

Invader’s core practice has always engaged the urban grid. Paris, Tokyo, São Paulo, Los Angeles—all have become laboratories for his coded visual experiments. In the city, his works function like micro-hacks within the urban flow, ephemeral yet archival, illegal yet curated by Instagram feeds and tourist selfies. But Rubik Camouflage, bound within the aluminum panel, is removed from this context. What was once an encounter is now an object; what was once interactive is now contemplative.

And yet, the studio version of camouflage sustains the tension. It simulates urban invisibility within the sterile cube of the gallery, folding into itself the contradiction of rebellion gone collectible. This self-awareness is crucial: Invader is not merely adapting for the art market, he is encrypting the contradiction. He builds within the grid to question the grid’s authority.

Camouflage as Cultural Critique

Camouflage is both literal and metaphorical here. Invader is a student of semiotics. In Rubik Camouflage, the artist cloaks meaning behind surface. In the military, camouflage is a strategy to avoid detection. In art, camouflage is often a conceptual ploy to critique detection itself—who sees, who is seen, and under what conditions?

Consider the political implications. Street artists are criminalized for visual expressions that governments cannot control. Camouflaging your identity, your intention, your hand—is not merely aesthetic, it is strategic. Invader, who has remained anonymous for decades, deploys anonymity not as gimmick but as praxis. In a post-Snowden world, Rubik Camouflage becomes a visual analogue to data encryption, a work that asks not “what do you see?” but “what do you miss when you think you see?”

Rubik’s Cube as Cultural Icon and Artistic Tool

The Rubik’s Cube—mass-produced, corporate, childlike—might seem an unlikely tool of cultural subversion. But it is precisely its ubiquity and perceived innocence that renders it effective. Like LEGO or Minecraft, it is both toy and language. Invader uses it not to solve a puzzle but to create one, reorienting the Cube from game to glyph.

By employing the Cube in a format such as Rubik Camouflage, Invader flips the logic of solvability. This is not a puzzle with a single answer, but a work that resists solution altogether. Its color choices are deterministic—limited by the Cube’s rigid palette—but its compositions suggest infinite permutations. The rigidity of the tool contrasts with the fluidity of its message. Thus, Rubik Camouflage becomes an essay in visual constraint, a manifesto of making within limitations.

Material Matters: Giclée and Aluminum

The decision to render Rubik Camouflage as a giclée print on aluminum is not incidental. Giclée printing, known for its archival quality and color fidelity, suggests a seriousness of craft. Combined with the aluminum composite panel—a material often used in architecture and industrial signage—the work acquires a visual gravity that contrasts with its playful origins.

Aluminum speaks to permanence, durability, and precision. It reflects not only light but also the conceptual weight of technological interface. It’s as if Invader is asking: what happens when the pixel becomes monument? When a tool of game and fun is fossilized into the language of permanence?

The New Archaeology of Street Art

What do we make of a work like Rubik Camouflage in 2025, when street art is no longer an insurgent act but a category at auction? Invader, alongside figures like Banksy, Shepard Fairey, and KAWS, has witnessed the transition from wall to white cube, from sticker to Sotheby’s. Yet Rubik Camouflage resists passive assimilation. It is not merely an image, but a glyphic artifact—a visual text waiting to be deciphered, interpreted, recontextualized.

Its camouflage is double: it hides within its own surface, and it hides within a market system that would love to neutralize its subversive potential. But like a virus, its message persists in the code. It remains insurgent not because it shouts, but because it whispers just out of reach.

Nostalgia, Encryption, and the Viewer’s Role

There is a deep nostalgia encoded in Invader’s pixelated universe—one that harks back to the early days of digital play, pre-internet innocence, coin-operated machines, joystick logic. But nostalgia here is not sentimental; it is tactical. Invader uses our emotional attachment to childhood symbols to lure us into critical reflection.

The viewer becomes a co-conspirator. You cannot passively absorb Rubik Camouflage. You must decipher it. Like the Rubik’s Cube itself, it requires rotation—mental, emotional, philosophical. You turn the colors in your mind, trying to see the figure emerge from the noise. But the camouflage holds. It wins. And in that loss, you’ve already entered Invader’s trap.

Flow

In Rubik Camouflage, Invader advances a complex thesis disguised in simplicity. He uses the most democratic of materials—a child’s toy, a mass-produced print—to speak to one of the most urgent questions of our era: how do we navigate visibility in a world where being seen is both a privilege and a peril?

Invader is not simply hiding behind pixels. He’s arming them. Each color, each square, each panel—strategically deployed to resist interpretation, resist commodification, resist simplicity. Rubik Camouflage is not about nostalgia. It is about coded survival. It is not about hiding. It is about deciding when—and how—to be found

No comments yet.