In the ever-shifting terrain of contemporary art, The Connor Brothers have established a defiant niche—somewhere between pulp fiction parody and sincere psychological excavation. Their 2019 piece “I Don’t Want to Go to Heaven” is not merely a witty pastiche of vintage Americana but a poignant statement draped in the ironic velvet of nostalgia, sexuality, and philosophical resignation. Beneath its playful aesthetics lies an arresting question about what it means to pursue joy in a world overwrought with disillusionment.

This editorial undertakes a literary and visual analysis of “I Don’t Want to Go to Heaven”, unpacking its artistic lineage, textual provocations, cultural resonance, and emotional undertow. In the broader landscape of the Connor Brothers’ work—where falsified identities, literary references, and tabloid glamor collide—this piece operates as both aphorism and altar, a shrine to the absurd logic of modern yearning.Who Are The Connor Brothers?

Before dissecting the artwork itself, it is essential to understand the mythos surrounding its creators. The Connor Brothers are the pseudonymous duo James Golding and Mike Snelle, who originally masqueraded as fictional twins raised in a Californian cult. This constructed biography was, in many ways, a conceptual extension of their artistic practice—a performance of persona, a critique of identity politics, and a romantic lie wrapped in the aesthetics of truth.

Emerging in 2013, their art blends Pop Art, textual provocation, and the visual language of mid-20th-century paperbacks and pulp magazines. Think Roy Lichtenstein meets Raymond Chandler. The result is a body of work that disarms through humor but lingers through emotional resonance.

“I Don’t Want to Go to Heaven”, completed in 2019, stands as a centerpiece of their creative ethos: seductive in form, subversive in content, and thoroughly of its time.

The Image as Fiction: Visual Composition and Vintage Lure

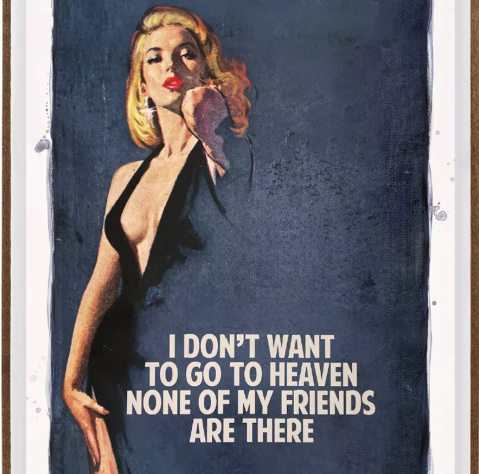

The visual structure of “I Don’t Want to Go to Heaven” is quintessential Connor Brothers: a repurposed image of a glamorous, idealized woman—straight out of a 1950s pulp novel cover—posing in partial undress, cigarette in hand, eyes suggestive of knowledge and melancholy. This imagery, airbrushed with vintage pastels and magazine realism, is deliberately chosen to evoke the tropes of mid-century escapism and eroticism.

But this isn’t homage—it’s critique masquerading as desire. The sexualized pose is not an invitation but a setup. Layered over the image in blunt white sans-serif typeface is the titular phrase:

“I don’t want to go to heaven. None of my friends are there.”

This one-liner, attributed (often apocryphally) to Oscar Wilde or Mark Twain depending on citation, becomes the anchor of the piece. It’s a barbed affirmation of earthly indulgence, a rejection of piety as a moral currency, and a confession disguised as cool.

Text as Truth: Aphorism as Emotional Philosophy

What gives “I Don’t Want to Go to Heaven” its emotional weight is not the image but the interplay between image and text. The quote does not exist merely for wit—it is the artwork’s thesis. The heaven in question is not theological but ideological: a place of clean living, correct behavior, and sanitized virtue. To declare “I don’t want to go” is to rebuff modern purity culture, social media perfectionism, and moral absolutism.

This phrase is emblematic of the Connor Brothers’ use of aphorisms. Their practice is rooted in the tradition of literary minimalism—one-liners that compress an entire worldview. In doing so, they align themselves with Dorothy Parker, Oscar Wilde, and Charles Bukowski: writers who wielded humor as scalpel and shield. The phrase becomes a kind of millennial koan—ironic, but not insincere; comic, but not hollow.

It also serves as a eulogy for modern alienation. Heaven is no longer a reward, but a place where we don’t belong.

Seduction and Irony: The Pulp Aesthetic as Contemporary Mirror

The Connor Brothers’ unique contribution to contemporary art lies in their repurposing of the pulp aesthetic—those lurid covers of dime-store novels that once thrived on titillation and taboo. Where these covers once promoted tales of adulterous housewives, noir detectives, and doomed dames, the Brothers insert existential laments, nihilist quips, and paradoxical truths.

By doing so, they undermine the objectification while utilizing its seductive power. In “I Don’t Want to Go to Heaven”, the viewer is drawn in by the promise of glamour—only to be confronted with ennui. This duality—seduction and confrontation—is the essence of postmodern irony. The artwork does not lecture; it winks. And in doing so, it becomes more persuasive than any sermon.

It’s art that wears mascara and smokes menthols while talking about Sartre.

Societal Reflection: Modernity, Rebellion, and Inner Hell

The year 2019 was a cultural watershed: politics in chaos, climate anxiety peaking, and digital identities fracturing under algorithmic strain. In that context, “I Don’t Want to Go to Heaven” takes on deeper meaning. It articulates a generation’s malaise—one that has grown skeptical of traditional notions of salvation, success, and stability.

To say “none of my friends are there” is not just a punchline—it’s a protest. It reclaims flawed humanity from the tyranny of virtue signaling. It accepts the broken, the bruised, the beloved degenerates.

Heaven becomes a metaphor for exclusion. The artwork challenges viewers to ask: who decides what constitutes moral worth? And more importantly, are we building communities of authenticity or judgment?

The Connor Brothers in the Contemporary Market

The Connor Brothers’ art has seen tremendous success in both primary and secondary markets. Their works are collected by celebrities, featured in international art fairs, and exhibited in top galleries. Their ability to merge accessibility with conceptual rigor has earned them a unique place—straddling high art and popular appeal.

But what makes their market relevance notable is the sincerity they sneak through the backdoor of irony. Collectors aren’t just buying witty pictures—they’re purchasing emotional ammunition. In a time when art is often expected to be either overly conceptual or commercially hollow, the Connor Brothers carve out a hybrid space.

“I Don’t Want to Go to Heaven” remains one of their most reproduced and celebrated images—not because it’s their boldest, but because it’s their most universal. It holds a mirror to everyone who’s ever wanted to be accepted not in spite of their flaws, but because of them.

Critical Reception and Enduring Influence

Critical reception of the Connor Brothers has evolved from skepticism to admiration. Early detractors dismissed their work as decorative, shallow, or overly reliant on borrowed imagery. But as their oeuvre expanded and their identity hoax was revealed to be a deeper commentary on trauma and reinvention (both artists battled addiction and depression), the emotional scaffolding of their work came into view.

Today, they are understood as conceptual tricksters who use kitsch as camouflage. Their influence is evident in younger artists who mix visual seduction with textual depth—artists exploring meme culture, AI aesthetics, and digital nihilism.

They are also part of a larger lineage that includes Barbara Kruger, Jenny Holzer, and Ed Ruscha—artists who use language as both object and meaning.

Impression: The Gospel According to No One in Particular

“I Don’t Want to Go to Heaven” is not just a painting—it’s a prayer for the misfits. A benediction for the beautiful wreckage of the human condition. It whispers what many are too scared to say aloud: that our sins, our scars, and our vices might be more honest than our virtues.

In the Connor Brothers’ universe, heaven isn’t the goal. The goal is connection, truth, and the freedom to be flawed. And that’s what makes this piece endure. It doesn’t offer answers—it offers belonging.

In a culture obsessed with improvement, “I Don’t Want to Go to Heaven” reminds us that some things don’t need to be fixed. They need to be framed.

No comments yet.