In the late autumn of 1882, a 29-year-old Vincent van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo, carving into the heart of his artistic struggle: “One must work long and hard to arrive at the truthful. What I want and set as my goal is damned difficult, and yet I don’t believe I’m aiming too high. I want to make drawings that move some people.” It was not an ambitious slogan. It was a confession. A hope written through fatigue. A line as honest and stripped as the drawings he was making in the Hague—sketches of miners, washerwomen, and crooked thatch-roofed homes clinging to the periphery of industrial life.

But it is in these words that Van Gogh reveals what would become the core of his legacy: a belief in the emotional weight of mark-making. A belief that truth in art was not intellectual, but sensory. That a line, if labored over long enough, could pulse with a heartbeat. That to “move some people” was not modest, but revolutionary.

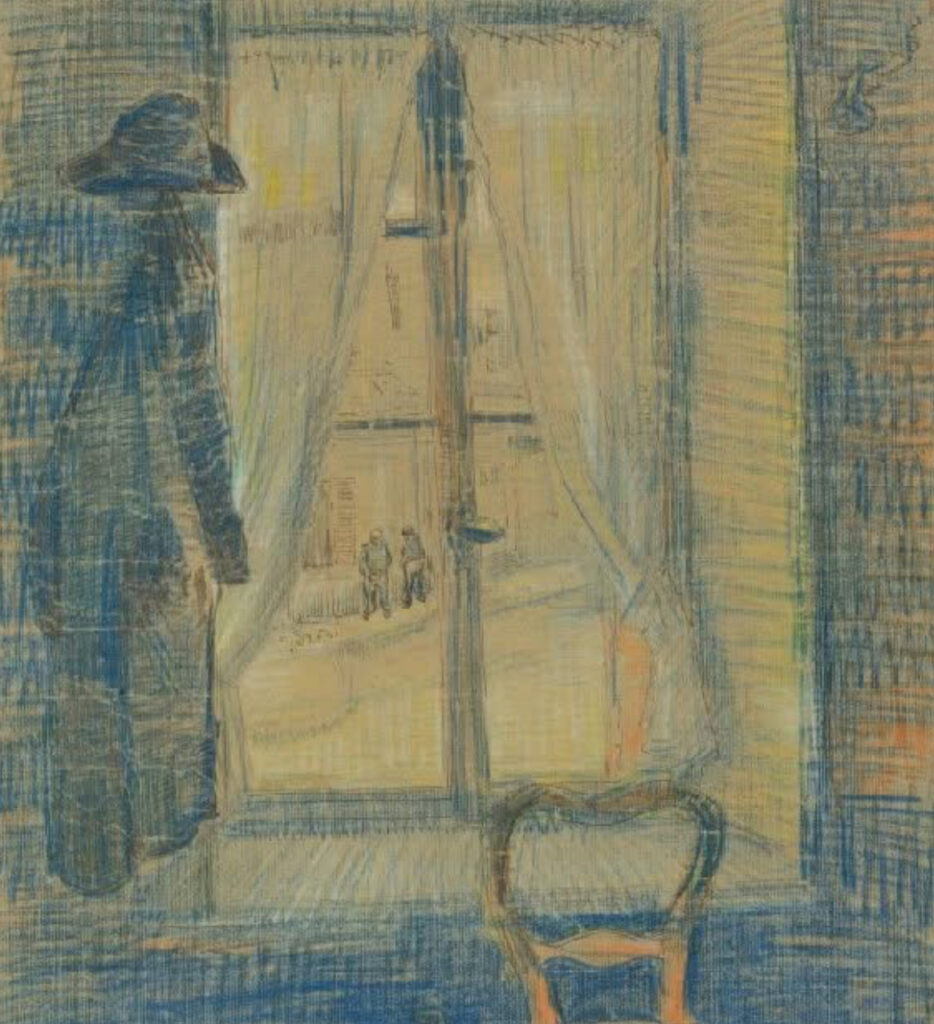

Nowhere is this philosophy more quietly distilled than in one of his lesser-known but deeply affecting works: Window in the Bataille Restaurant (1887). Not a sunflower, not a starry sky, not a self-portrait pierced by his own relentless gaze—but a window. Framed simply, rendered plainly. Yet behind that modest composition lies the full complexity of Van Gogh’s pursuit of what he called the truthful.

A Quiet Threshold: Reading the Window

In art, the window has always been a potent symbol—both literal and allegorical. It offers a threshold between inside and outside, a boundary that is both barrier and bridge. For Van Gogh, windows often served as moments of introspective geometry. They’re not escape routes; they’re meditative structures.

Window in the Bataille Restaurant belongs to Van Gogh’s Paris period, a time of enormous transformation. Having arrived in the city in 1886, he was absorbing influences from Impressionism and Japanese woodblock prints. His palette brightened, his brushwork accelerated. But this work, painted just a year into his Parisian life, stands apart. It is not flamboyant. It does not dazzle with color. Instead, it gazes. It waits.

The window in question is tightly composed. Its panes dissect the canvas with quiet precision, each square reflecting snippets of light and blur from the world beyond. There is a curtain, half-pulled. The brushwork is subtle—dry and dry-brushed, revealing the linen beneath. And behind it, the city rests as suggestion: diffuse light, spectral buildings, something that could be a tree, or smoke, or a thought.

It is not grand. But it is deeply felt. It is the kind of painting one returns to with increasing attention—finding, in its simplicity, an emotional calibration that few artists ever master. This is a window not just into the world, but into Van Gogh himself: his temperament, his need for observation, his longing to locate tenderness in the ordinary.

The Labor of the Truthful

What Van Gogh seeks in this window is not realism. He is not concerned with optical precision. What he wants is resonance. And resonance, for Van Gogh, comes through effort. That is why the line about “work[ing] long and hard” matters so much. It is not romantic agony—it is aesthetic devotion.

We often associate Van Gogh with fevered spontaneity—mad dashes of color, brushstrokes like knife wounds. But that reading risks overlooking how measured and deliberate he often was. In the early 1880s, he studied anatomy, perspective, and chiaroscuro with rigorous focus. His sketchbooks from the period are filled with studies that border on architectural. Window in the Bataille Restaurant is the fruit of that discipline.

In this work, Van Gogh reclaims the window not as a motif but as a vessel for inner life. He paints not what the window sees, but what it feels like to look through it on a day where the light is neither celebratory nor tragic. The tone is contemplative. The silence in the room just behind the window is almost audible.

That’s the essence of his truthfulness: not to render the world as it is, but to offer it as it feels. As it presses against the skin of our days.

From the Café to the Cosmos

The Bataille Restaurant was no landmark. Situated in Montmartre, it was the kind of working-class café that filled the Paris of the 1880s with the scent of bread, wine, and fatigue. Van Gogh often visited such places—not for spectacle, but for the shape of lived moments. These interiors offered him something churches could not: proximity to laborers, loners, and ordinary grace.

Painting its window is an act of reverence. It says, “this place matters.” It says, “there is beauty here.” In doing so, Van Gogh anticipates one of the core tenets of modern art—that the subject does not have to be monumental to be meaningful. A window can be enough. A curtain, slightly drawn, can become a story.

That same year, Van Gogh would begin experimenting with color in more dramatic ways. The cobalt shadows of Le Café de Nuit. The vibrating greens of Portrait of Père Tanguy. But Window in the Bataille Restaurant is the quiet before the bloom. The heartbeat before the roar.

The Emotion of Observation

The painting’s most radical quality, perhaps, is its restraint. In an age of increasingly expressive brushwork, Van Gogh offers stillness. But it is a stillness earned through looking—a kind of emotional observation.

It brings to mind what the poet Rainer Maria Rilke wrote about looking at things: “If your daily life seems poor, do not blame it; blame yourself that you are not poet enough to call forth its riches.” Van Gogh, it seems, was poet enough. He found riches in shadows. In blurred glass. In the half-light of a Parisian afternoon filtered through café windows.

In this sense, Window in the Bataille Restaurant is not merely a painting—it is a pause. A kind of visual haiku. A lesson in humility and perspective. It asks nothing but attention. And for those who offer it, the reward is profound.

A Letter, a Line, a Legacy

We return, then, to that letter to Theo. To the declaration of difficulty. The confession that art is hard. That moving people is hard. But that it is worth the effort. In those words, we find the spine of Van Gogh’s vision.

He was not after fame—he never lived to see it. He was not after innovation for its own sake. What he wanted was contact. An emotional spark. A drawing that moves someone. A painting that doesn’t announce itself, but lingers.

And that is precisely what Window in the Bataille Restaurant achieves. It does not dazzle. It does not demand. But it stays. It becomes part of one’s inner architecture. It reminds us that a window is not just an object—it is a proposition. It offers both exit and entry. It lets light in and reveals what we choose to see.

Postscript: Looking Through, Not At

In the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, where Window in the Bataille Restaurant now quietly resides, most visitors rush to the sunflowers, the irises, the self-portraits. And rightly so. These are masterworks of passion and despair and beauty.

But somewhere on the wall, this small, unassuming window waits. It does not scream for attention. But it rewards it.

To stand before it is to practice what Van Gogh practiced: seeing with feeling. Drawing with care. Believing that even the smallest subject—rendered truthfully—can move someone.

In that sense, the painting is not just about a window. It is a window. And through it, we see not only the world outside—but the world within.

No comments yet.