One of the more peculiar and notorious episodes in literary history took place in 1937, when Ernest Hemingway, the celebrated novelist, physically assaulted fellow writer and critic Max Eastman by slapping him in the face with a book in the offices of the prominent publishing house Charles Scribner’s Sons. This bizarre altercation between two literary heavyweights is more than just a humorous anecdote. It represents the fiery temper of Hemingway, his insecurities about his own masculinity, and the often contentious dynamic between authors and critics. The incident encapsulates the tension between creative genius and public scrutiny, and the clash of two distinctly different personalities whose egos collided in a dramatic fashion.

The Build-Up: Hemingway and Eastman’s Literary Relationship

The infamous encounter between Hemingway and Eastman didn’t materialize out of thin air. It was the result of simmering tensions and a harsh literary critique that struck at the heart of Hemingway’s most sensitive nerve—his reputation as a man’s man.

By the time of the incident, Hemingway had already established himself as one of the foremost writers of his generation, celebrated for works like “The Sun Also Rises” (1926) and “A Farewell to Arms” (1929). His terse prose, distinct style, and depictions of war, masculinity, and heroism had earned him widespread acclaim. However, alongside the accolades came increasing criticism, and many intellectuals were critical of what they saw as Hemingway’s overemphasis on masculinity and the caricature of toughness in his work.

Enter Max Eastman, a writer and social activist known for his intellect, sharp wit, and outspoken opinions. In 1937, Eastman published a critique of Hemingway in “The New Republic” titled “Bull in the Afternoon,” a play on Hemingway’s famous book “Death in the Afternoon” about bullfighting. In his piece, Eastman accused Hemingway of being overly obsessed with the idea of masculinity, suggesting that his writing was compensating for insecurities in his own manhood. He described Hemingway as “wearing false hair on his chest,” implying that the writer’s persona of rugged masculinity was nothing more than a facade. The critique struck a chord with Hemingway, whose public image and personal identity were deeply intertwined with the concept of the macho writer adventurer.

The Confrontation: Slaps, Desks, and Masculine Pride

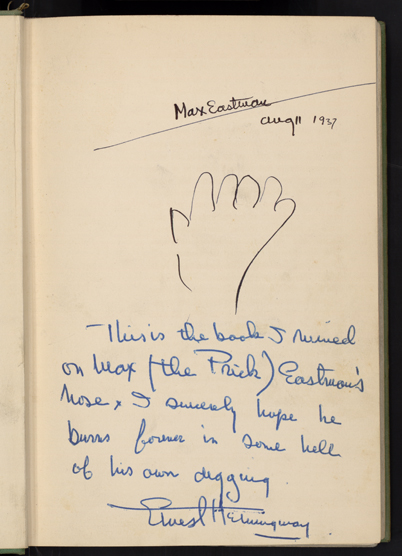

It wasn’t long before Hemingway would have his chance to confront Eastman in person. In August 1937, both men found themselves in the New York offices of Charles Scribner’s Sons, the publishing house responsible for Hemingway’s work. Scribner’s office was meant to be a professional and intellectual space, but on that day, it turned into an arena for a very personal and physical altercation.

Accounts of the incident vary slightly, but the general details remain consistent. Upon encountering Eastman at the publisher’s office, Hemingway, still fuming over the “false hair on his chest” remark, began to berate him. Eastman, who was more of an intellectual sparring partner than a physical one, may not have expected Hemingway’s confrontational style to take such an aggressive turn.

At the height of the confrontation, Hemingway picked up a copy of “Maxim Gorky: Man and Artist”, a book written by Eastman, and slapped him across the face with it. The act was both shocking and theatrical, a perfect embodiment of Hemingway’s volatile temperament. As if to prove that the critique had gotten under his skin, Hemingway’s violent response could be seen as his way of asserting his own version of masculinity—one that relied not on intellectual debate, but on brute force.

Eastman’s reaction, according to his own retelling, was to defend himself physically. He claimed that after the initial slap, he threw Hemingway over a desk and stood him on his head in a corner of the room. While this account has often been repeated, it is impossible to verify the exact details. Still, Eastman’s version paints the picture of an intellectual forced to resort to physical retaliation, besting the physically imposing Hemingway in a somewhat ironic twist of fate.

The Aftermath: Literary Gossip and Lingering Resentment

The book-slapping incident between Hemingway and Eastman quickly became the subject of gossip in literary circles. Both men were public figures, and their clash was seen as a dramatic manifestation of the strained relationship between artists and their critics. For Hemingway, the incident was likely an embarrassment, further fueling the notion that he was overly concerned with proving his manliness. For Eastman, it was a validation of his critique—he had touched a nerve, and Hemingway’s reaction only reinforced the idea that his masculinity was fragile, more posturing than reality.

Despite the physical altercation, neither man’s career suffered in the aftermath. Hemingway would go on to solidify his place as one of the most important writers of the 20th century, winning the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1954. Eastman, while not as iconic a literary figure as Hemingway, maintained his position as a respected intellectual and critic, continuing to publish essays and critiques well into the later years of his life.

However, the incident left a lasting impression on both men’s legacies. For Hemingway, it became one more story in a long list of anecdotes illustrating his infamous temper and sensitivity to criticism. It also played into the larger narrative of his life, which was filled with struggles over how to portray masculinity in his work while reconciling his own personal insecurities. Eastman, on the other hand, came out of the confrontation looking like the intellectual who had bested the famous writer, both with his pen and in the physical realm. His critique of Hemingway’s masculinity became part of the mythos surrounding the author.

A Clash of Egos and Ideals

The 1937 book-slapping incident between Ernest Hemingway and Max Eastman remains one of the more curious and entertaining moments in literary history. What might have been a simple disagreement between an author and a critic turned into a physical altercation, revealing the deep-rooted insecurities Hemingway harbored about his masculinity. At its core, the confrontation highlights the often contentious relationship between creators and their critics, especially when it comes to matters as personal as one’s public image and identity.

In the end, the incident serves as a reminder that even the greatest writers are not immune to the pressures of public perception and criticism. Hemingway’s fiery reaction, though dramatic, was emblematic of the thin line many artists walk between confidence and vulnerability. And for Eastman, the altercation was proof that the pen—and sometimes the body—can indeed be mightier than the sword.

No comments yet.