June 6, 2025, marks the eighty-first anniversary of the D-Day invasion—Operation Overlord—one of the most ambitious and consequential military undertakings in modern history. It was not simply a clash of armies but a pivot of destiny. The Allied invasion of Nazi-occupied France, launched on June 6, 1944, was more than a military campaign; it was a thunderous declaration against tyranny, a gamble of staggering scale, and a human endeavor measured not only in blood, but in silence, waiting, and weight.

Among the many artifacts and records left behind from that monumental day—maps, communiqués, rusted helmets, torn letters—there exists one item unlike the others. It is not a strategy memo or a battlefield dispatch. It is a short, handwritten note, less than a paragraph long. Folded carefully, it rode silently in the wallet of one man. A man upon whose shoulders rested not only the strategy of the greatest amphibious invasion in history, but the psychic weight of possible failure.

This note was never read to the public. It was never needed. But it was written. And that fact alone reveals something profound—not only about the man who wrote it, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force—but about the nature of leadership in moments when history holds its breath.

“The Eyes of the World Are Upon You”

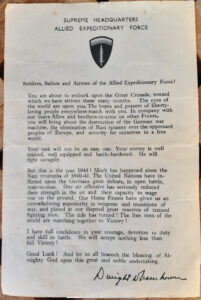

In the hours before the first boots touched sand, before the roar of Higgins boats crashing into the surf, before parachutes bloomed like ghostly flowers over Normandy’s fields, Eisenhower addressed his troops. In his now-famous Order of the Day, dated June 6, 1944, he declared:

“Soldiers, Sailors and Airmen of the Allied Expeditionary Force! You are about to embark upon the Great Crusade, toward which we have striven these many months… The eyes of the world are upon you.”

These words were not poetic abstraction. The eyes of the world were upon them. The enslaved populations of Europe, held in the iron fist of the Nazi regime, looked west with desperate hope. Every soldier knew that failure meant not just defeat, but prolonged global darkness.

Eisenhower’s message was clear: the mission was righteous, the planning meticulous, the cause just. But privately, he had no illusions. He knew that military perfection was a fantasy. Weather could betray them. Intelligence could mislead. The enemy could surprise. And so, in the solitude of command, he wrote a second note.

“My Decision to Attack”: The Contingency Letter

“Our landings in the Cherbourg-Havre area have failed to gain a satisfactory foothold and I have withdrawn the troops.

My decision to attack at this time and place was based upon the best information available.

The troops, the air, and the Navy did all that bravery and devotion to duty could do.

If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt it is mine alone.”

These words, written in pencil, shaky and hurried, are now preserved in the Eisenhower Presidential Library. They were never delivered, never spoken. But they might be the most revealing thing Eisenhower ever wrote.

Originally, the draft read: “This particular operation has failed.” But Eisenhower crossed out “This particular operation,” replacing it with: “My decision to attack.” That edit changes everything. The blame doesn’t belong to some abstract event. It belongs, in Eisenhower’s own hand, to him.

This was not political posturing. There were no cameras, no journalists, no court of public opinion. It was a message he wrote only for use in the most catastrophic of scenarios—a full retreat under fire, with untold casualties, with Europe left shackled and Hitler triumphant. That message was his shield for the men under his command. And it stayed in his wallet, close to his heart, as the armada crossed the English Channel.

The Human Cost of Command

Leadership is often praised in grand terms: vision, charisma, decisiveness. But D-Day demanded something else: acceptance of unbearable possibility. Eisenhower bore that silently.

Think of it: more than 150,000 Allied troops staged across southern England, ready to storm beaches defended by concrete bunkers, machine-gun nests, and tangled steel. Weather reports fluctuated wildly. Commanders disagreed on timing. Airborne troops faced scattered drops into unknown terrain. German reinforcements waited inland.

Eisenhower’s advisors were divided. Some pushed for delay. Others feared delay would mean permanent cancellation. Ultimately, he made the call: Go.

And having made that decision, he prepared to take the full weight of its consequences. He did not draft a shared statement with other generals. He did not hedge or suggest shared responsibility with Churchill, Roosevelt, or de Gaulle. He wrote plainly: “If any blame or fault attaches… it is mine alone.”

In that single sentence, Eisenhower revealed what true command looks like—not just authority over others, but accountability for them.

Imagining the Alternate Timeline

Let us pause, just for a moment, and consider the other world—the one in which the note is not folded quietly away, but spoken aloud in a trembling voice before a stunned press corps.

Imagine: the skies over Normandy remain stormed in; the paratroopers are scattered and slaughtered in the hedgerows; the landing craft become floating coffins; the beachhead collapses under withering German fire. Bodies pile in the surf. Supply lines choke. The invasion crumbles. And then, days later, Eisenhower, pale and sleepless, reads the note. A world hoping for liberation sinks into despair.

We do not live in that world. But Eisenhower did—if only in his mind. He looked it square in the face. He prepared for it. That alone makes him remarkable.

Eisenhower the Man, Not the Monument

Today, Eisenhower is often remembered as a figure of myth—President, liberator, smiling face of mid-century optimism. But in 1944, he was something harder to categorize. He was a general without a battlefield command, coordinating not just troops but nations—British, Canadian, American, Free French, Polish. He was a diplomat and a strategist, but also a man who visited wounded paratroopers in the hospital, who walked alone through lines of sleeping soldiers the night before the invasion.

He wasn’t above self-doubt. In fact, he carried it with him.

That’s the value of the note. It pierces through the polished marble of memory and shows us a man under pressure beyond measure—aware of history’s gaze, yes, but also its weight.

In that note, there is no deflection. No bureaucratic buffer. Just a pencil, paper, and the plain voice of accountability.

Legacy in Lead and Silence

Eisenhower never read that contingency letter aloud. D-Day, for all its initial chaos, succeeded. The Allies secured the beaches, albeit at horrific cost—over 4,400 confirmed dead in the first 24 hours. But the beachhead held. The push into France began. The road to Paris and Berlin was bloody but opened.

The note, tucked away, was never needed. Yet that absence has become its own kind of presence.

Historians marvel at its brevity, its clarity, its humility. In an age of political maneuvering and blurred lines of responsibility, Eisenhower’s note has become an ethical touchstone—cited in leadership seminars, military academies, and crisis planning sessions. Not as an act of self-promotion, but as an act of radical ownership.

It’s one thing to win history’s battles. It’s another to face the ones you might lose, and still step forward.

81 Years Later: What Remains

Eighty-one years have passed since the beaches of Normandy turned red with sacrifice. Today, those beaches are quiet—wind-swept, grassy, dotted with white crosses. The veterans are fewer, older. The stories are passed now by descendants, historians, and teachers. And yet, some truths remain vivid.

The valor of the troops. The scale of the risk. The darkness they charged into. And yes, the note.

Because in that small piece of paper, Eisenhower gave us more than a footnote in history. He gave us a standard.

In a world hungry for leadership, for responsibility, for the courage to admit when things go wrong, that note is a rarity. It is unvarnished. Unpublished at the time. And absolutely sincere.

Leadership is often described by what happens when things go right. But Eisenhower understood that it is more truly measured by what one is prepared to do when they go wrong.

And that’s why we remember not just the invasion, but the possibility that it might have failed—and the man who was willing to say, If it does, the fault is mine.

Sources and Further Reading:

- Eisenhower Presidential Library – Manuscript of the Contingency Note

- “D-Day: June 6, 1944” by Stephen E. Ambrose

- Official Records of Operation Overlord (U.S. National Archives)

- Interviews with surviving veterans compiled by the National WWII Museum

No comments yet.