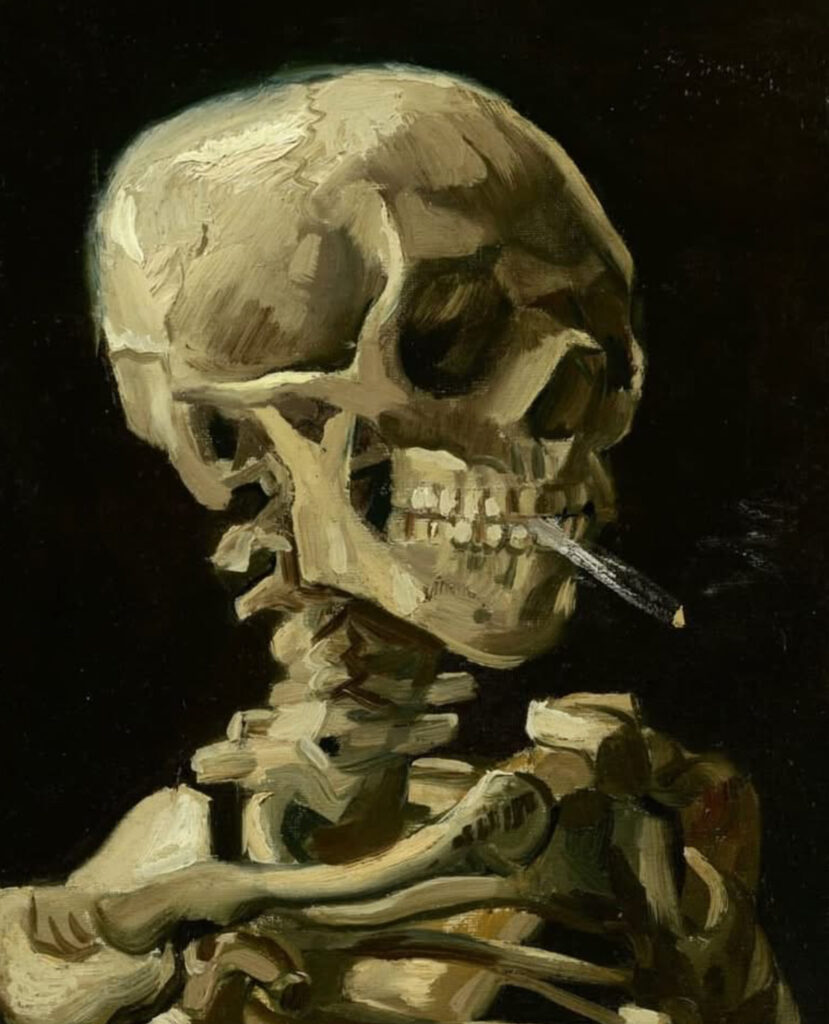

In the well-lit pantheon of Vincent van Gogh’s iconic works—sunflowers, irises, starry nights, and stoic self-portraits—there exists an anomalous outlier: Skeleton with a Burning Cigarette (1886). At first glance, the small canvas, depicting a human skull calmly puffing on a lit cigarette, feels satirical, even mordant. But beneath its mischievous surface lies a disquieting prelude to the artist’s descent into isolation, illness, and existential inquiry.

This bone-dry figure, both anatomical and animated, occupies a strange space in Van Gogh’s oeuvre. It was painted while the artist was studying in Antwerp—a period of artistic transition, bodily hardship, and psychological unrest. Though seemingly minor in scale and visibility compared to his later masterpieces, Skeleton with a Burning Cigarette is, in many ways, Van Gogh’s first truly subversive gesture.

The Anatomy of Irony: Van Gogh in Antwerp

Van Gogh painted Skeleton with a Burning Cigarette in the winter of 1886 while enrolled at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp. It was a brief and fraught period in the artist’s life. Struggling with poverty, malnutrition, and a deteriorating set of teeth, Van Gogh found little inspiration in the rigid academic structure he encountered. The traditional methods of training—particularly the use of anatomical skeletons for drawing practice—felt stale and impersonal to the fiercely emotional Dutchman.

Against this backdrop, the painting reads as both satire and subtle rebellion. The skeleton, rendered with delicate precision and almost classical restraint, suddenly breaks protocol: it smokes. The cigarette, its ember glowing faintly in Van Gogh’s otherwise muted palette, transforms the academic exercise into a darkly comedic visual pun. Death is not solemn here; it is flippant, irreverent, alive.

And this irony, cloaked in smoke, is the very substance of Van Gogh’s humor—macabre, reflective, and tragically aware.

Death, Delirium, and Dismissal

Much has been made of the work’s tone. Is it a joke? A protest? A bleak self-portrait in disguise?

Some scholars view Skeleton with a Burning Cigarette as nothing more than a student prank—a visual punchline aimed at the antiquated curriculum he was forced to endure. Others perceive it as the first brushstroke in a longer meditation on death and deterioration that would follow Van Gogh until his last days in Auvers-sur-Oise.

The timing is significant. By 1886, Van Gogh had already experienced intense bouts of physical illness and psychological distress. His smoking habit—documented throughout his letters—had worsened. He was living largely on bread and coffee, supplemented occasionally by alcohol and tobacco. The skeletal figure, then, might be less symbolic of universal mortality and more an intimate reflection of Van Gogh’s own emaciated, weakened body.

In this reading, the painting becomes almost diagnostic. The skeleton is not simply dead; it is actively dying. And yet, it smokes.

The Cigarette: Modernity’s Memento Mori

Unlike the scythe or the hourglass in classical vanitas paintings, Van Gogh’s cigarette is not a timeless symbol. It is resolutely modern. The cigarette, industrial and recent in 19th-century Europe, signifies not just death but the manner in which people invite it—casually, willfully, perhaps even stylishly.

In placing the cigarette between the skeleton’s teeth, Van Gogh is not merely being humorous—he’s being nihilistic. This is death enjoying its own inevitability. There is no lesson, no moral, no symbolic resurrection. Only ash.

One could argue that the cigarette in Skeleton with a Burning Cigarette operates as a visual precursor to the artist’s later fixation on withering, scorched landscapes and decaying sunflowers. Fire, both literal and metaphorical, smolders through Van Gogh’s work. Here, it is but a glowing tip of defiance—daring, laughing, disappearing.

The Skull and the Self-Portrait

There is a longstanding art historical tradition of artists painting skulls to reflect on mortality and the futility of ego. Van Gogh, always attuned to emotional candor, refrains from overt symbolism. And yet, in its rendering, this skeleton almost possesses personality. Its teeth curl subtly into a smirk. Its eye sockets seem alert. The angle of the head—slightly tilted—evokes thought, even amusement.

Some critics have speculated that this could be a veiled self-portrait. While not formally confirmed, the reading is seductive. What if this skeletal smoker is not just any skull, but his skull? What if Van Gogh, bone-thin and hollow-eyed during his Antwerp days, imagined the shape of himself posthumously, already consumed by the inward flame he knew would never be extinguished?

If ever intended or not, the intimacy of the image suggests more than a random anatomical exercise. It suggests interiority—humor, exhaustion, resignation. It is the grin of someone who has stared down the void and decided to keep drawing.

From Bones to Blossoms: An Evolution

What makes Skeleton with a Burning Cigarette especially fascinating is how uncharacteristic it is compared to the canonical Van Gogh. There are no swirling skies, no vibrating brushwork, no symbolic use of color. The background is flat, the skeleton stark. And yet, this oddity provides the seedbed for Van Gogh’s later breakthroughs.

From these bones would rise the Sunflowers, the Café Terraces, the Wheatfields, and ultimately, the Starry Night. In this early work, Van Gogh had not yet discovered his signature stroke, but he had discovered something just as vital: tone. Skeleton with a Burning Cigarette is a painting of atmosphere, not just anatomy.

A Laugh Before the Fall

Perhaps most haunting about the painting is its simultaneous lightness and finality. It laughs, but it is not laughing. It lives, but it is already dead. It flickers in that liminal space Van Gogh would occupy for the rest of his career—between brilliance and breakdown, between gesture and surrender.

Today, housed in the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, Skeleton with a Burning Cigarette remains one of the artist’s most visited yet least understood works. Visitors tend to chuckle at first. But the longer they look, the less funny it becomes. That’s its genius. Like the best of Van Gogh, it lingers.

No comments yet.