Art often begins with a gesture of transformation: something overlooked becomes elevated, something old becomes new, something lost becomes visible. In Pressed Blouse (2005), Jean Shin performs such a gesture with haunting elegance. Using her own garment—a well-worn blouse—as both subject and medium, she imprints absence onto paper through the technique of collagraphy. The result is not simply an image, but a trace. A tactile ghost. A vestige of intimacy made strangely monumental.

This artwork, deceptively modest in appearance, is a pivotal exemplar of Shin’s enduring interest in the materiality of memory, the sculptural potential of discarded objects, and the quiet politics of everyday life. Pressed Blouse is not just a print—it is a relic. And within it, Shin explores themes of identity, labor, fragility, and personal archaeology, all pressed—literally and metaphorically—into the fibers of her practice.

CLOTH AS LANGUAGE, FIBER AS WITNESS

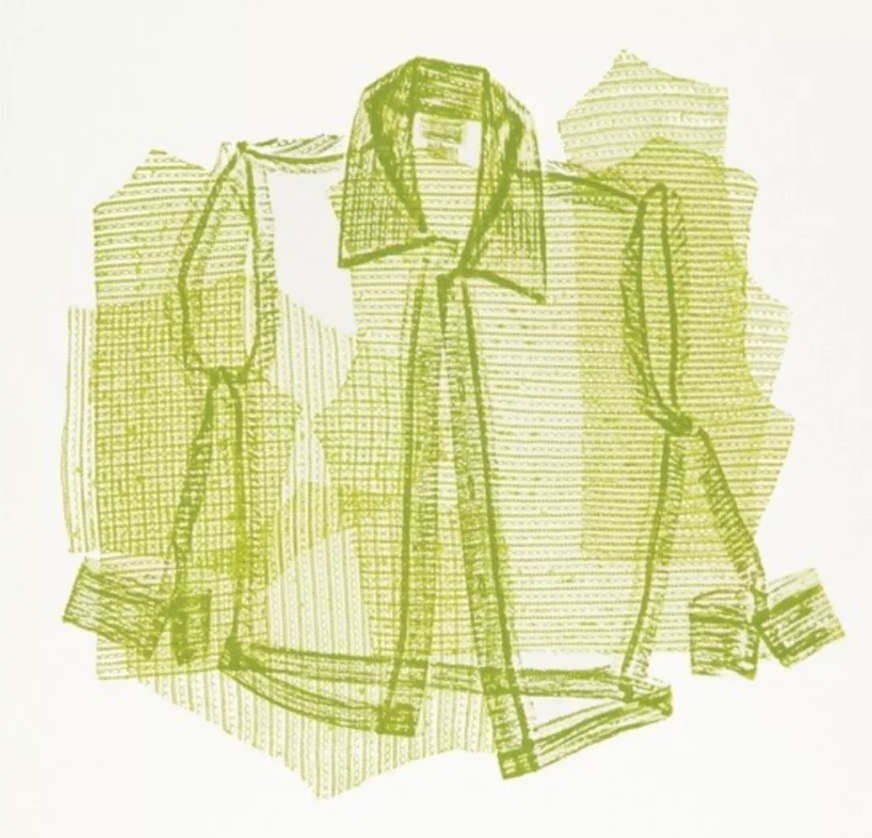

Jean Shin’s Pressed Blouse is made using a collagraphic process—a form of printmaking that emphasizes surface texture and relief. But unlike traditional collagraphs, which might be built from mixed materials or found textures, Shin’s plate is deeply personal: her own blouse. Pressed and inked, it becomes both tool and trace, a memory-object made visual.

There is something incredibly intimate about this decision. Clothing is one of the closest extensions of the self, a second skin. It carries the shape of the body, the scent of its wearer, the rhythm of daily gestures: a rolled cuff, a stretched collar, a smudge of pigment. In pressing her blouse into permanence, Shin transforms an ordinary act—folding laundry, ironing a shirt—into a ritual of reflection.

But this is not an act of vanity or preservation. The blouse is not displayed as a relic of importance, but rather flattened into a visual echo. Its contours are subtle, its texture ghostly. There are no vibrant hues or flashy details. The print is monochromatic, almost funereal. In this restraint lies its power. Shin does not ask us to admire the blouse, but to feel it—its absence, its presence, its soft endurance.

THE BODY THAT ISN’T THERE

One of the most striking features of Pressed Blouse is what it withholds. There is no figure in the print, no human form. And yet, the body is everywhere—implied in every crease, every stretched seam. The garment, now emptied of the person who wore it, becomes a kind of stand-in. A portrait not through likeness, but through residue.

This strategy echoes the aesthetics of absence that define much of Shin’s oeuvre. Whether working with broken umbrellas (Everyday Monuments), empty prescription bottles (Chemical Balance), or discarded shoes (Textile Grid), Shin constructs human presence through its aftermath. Her art operates in the wake of use—after the wearing, after the discarding, after the forgetting.

In Pressed Blouse, the absent body becomes a site of meditation. It suggests aging, care, repetition. The print feels both deeply personal and quietly universal. Who among us hasn’t had such a garment—worn until thin, meaningful not for its style but its tenure? A blouse worn through seasons of work and life, love and laundry. The body that wore it is gone, but it leaves behind an impression—faint, worn, enduring.

PRINTMAKING AS RESISTANCE

There is a quiet radicalism in Shin’s use of printmaking. Historically, printmaking was a democratic medium—one that allowed for multiples, for dissemination. Shin’s prints, however, reject repetition. Each collagraph, made from a specific object or material, resists mass production. Pressed Blouse is singular, fragile. It cannot be exactly recreated, because its matrix—the blouse—will inevitably break down. The plate is temporary. The print is its only enduring form.

In this way, Pressed Blouse critiques the logic of mass production, the disposability of materials, and the homogenization of identity. It insists on singularity. On story. On labor. It is an anti-industrial object, made through a slow and tactile process that mirrors domestic work itself—pressing, folding, touching, caring.

Shin, a Korean American artist who immigrated to the United States at a young age, understands deeply how identity is mediated through material culture. Her use of printmaking isn’t about aesthetic replication—it’s about preservation through erosion. She records what is vanishing, before it disappears altogether.

GENDERED MATERIAL, GENDERED MEMORY

Clothing, especially that worn by women, has historically been excluded from the canon of “serious” art. Too domestic. Too soft. Too sentimental. Shin’s work dismantles this hierarchy. In Pressed Blouse, she elevates the personal to the architectural. The blouse is no longer just fabric—it becomes a topography of emotion, a sculptural field of memory.

There is also a feminist critique embedded here. The blouse—often coded as feminine, professional, caretaking—is a symbol of gendered labor. It is worn to work, to serve, to present. By pressing it into permanence, Shin acknowledges the work that women’s clothing does: to contain, to protect, to conform, to resist.

The flatness of the print reads almost like a shroud. It is not vibrant or joyous—it is elegiac. And yet it does not mourn. It dignifies. The blouse becomes monument, not memorial.

THE DOMESTIC AS MONUMENTAL

Throughout her career, Jean Shin has explored the sculptural potential of the domestic. Her installations often use everyday materials—eyeglasses, sweaters, worn shoes—not for their novelty, but for their accumulative weight. They build narratives through volume, repetition, and subtle variation.

Pressed Blouse condenses that strategy into a single object. It is quiet, but no less monumental. In fact, its power lies precisely in its humility. It asks the viewer to look closer, to dwell in texture, to feel the smallness of a sleeve or the asymmetry of a collar.

In a gallery space, this work might go unnoticed amid louder, more colorful pieces. But that’s the point. Shin’s art requires stillness. It rewards intimacy. It shifts the scale of importance from the heroic to the habitual. A pressed blouse becomes a site of reverence—not because of who wore it, but because it was worn.

EVIDENCE OF CARE

Care is a central theme in Pressed Blouse. To press a blouse is to care for it. To print it is to record that care. The artwork is not only about what the blouse represents, but how it has been treated. It has been preserved—not by being framed or archived, but by being transformed. It has moved from utility to image, from body to trace.

In this transformation, we are reminded of the labor that goes unseen: the washing, the ironing, the folding. The daily acts of maintenance that hold families together, that pass unnoticed until something is missing. Shin does not romanticize this labor—she reveals its quiet dignity.

There is also a deep sense of gratitude embedded in the work. Acknowledgment. The blouse was not chosen because it was new or beautiful. It was chosen because it was lived in. Because it meant something. Shin thanks it not with words, but with permanence.

Impression

All of Jean Shin’s works are memory objects. They hold time. They gather fragments. They resist forgetting.

Pressed Blouse is perhaps the most distilled version of this ethos. It is not nostalgic—it does not look backward with longing. It looks inward. It holds space. It says: this was here. This mattered.

In an era of digital acceleration, such gestures are rare. We do not pause to press. We do not pause to remember. Shin’s work slows us down. It draws us back to the tactile, to the domestic, to the personal histories written in seams and folds.

The blouse, in its pressed and printed form, becomes not just a symbol of the past—but a vessel of presence. It asks us to attend, to witness, to feel.

No comments yet.