In the pantheon of contemporary hyperrealism, few artists walk the line between indulgence and interrogation as deftly as CJ Hendry. Known for her obsessive ink drawings of everyday objects—rendered in such extraordinary detail that they disorient more than impress—Hendry’s practice straddles commerce, compulsion, and critique. She draws with the patience of a surgeon and the precision of a machine, yet her work speaks deeply to the tactile hunger of a digital age.

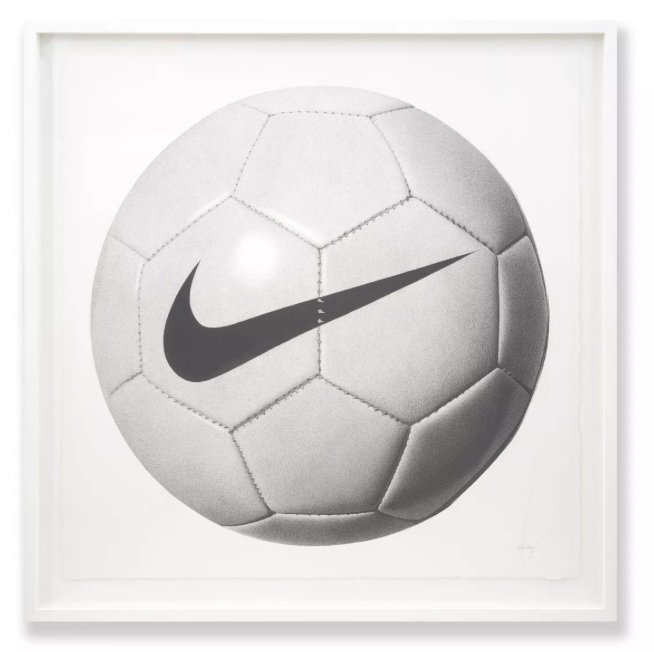

Among her early works, Nike Ball (2014)—a deceptively simple ink-on-paper drawing of a Nike-branded basketball—stands out as a seminal gesture. In this piece, Hendry doesn’t just draw a ball. She distills it, elevates it, monumentalizes it. Through hundreds of hours, layers of black ink, and a stark white background, she transforms a mass-produced object into a reliquary of both cultural symbolism and personal fixation.

Nike Ball is not merely a technical feat. It is a thesis. A study in the aesthetics of branding, the fetishization of sport, and the strange quietness of photorealism at its most extreme. The result is not a drawing of a basketball. It is the basketball, reimagined as both object and icon.

Hyperrealism as Tension, Not Spectacle

The immediate response to Nike Ball is disbelief. Is it really a drawing? How can ink—messy, pooling, imprecise—be tamed into such velvety, dimensional form? Hendry’s photorealism doesn’t merely mimic the real; it amplifies its material truth. Every leather dimple, every groove of the rubber, every subtle shift in light across the ball’s surface is not captured but rebuilt.

But this realism is not neutral. It creates a tension: between the flatness of paper and the depth of illusion, between the everyday object and its aesthetic canonization. Hendry draws not to replicate reality but to heighten it to the point of discomfort. Her surfaces gleam. They sweat. They become intimate. The viewer doesn’t just observe the object—they begin to sense its weight, its silence, its cultural gravity.

In Nike Ball, the blackness of the ink almost absorbs the viewer’s gaze. The logo—Nike’s iconic Swoosh—sits like a corporate scar, familiar yet oddly menacing in its hyper-detail. The ball becomes more than itself. It becomes an emblem of athletic mythology, capitalist repetition, and the near-religious aura of brand culture.

Ink and Obsession: Labor as Medium

What elevates Nike Ball from masterful draftsmanship to conceptual artwork is its obsessive labor. Hendry’s choice of ink—particularly ballpoint pen or fine pigment ink—forces total commitment. It cannot be erased. It cannot be layered infinitely. Every stroke is final. The surface of her paper, often white and museum-grade, must remain pristine, unbent, unsmudged. The process is almost violent in its discipline.

She has spoken of her work as “a kind of punishment.” This is not performance. It is devotional. Each drawing takes hundreds of hours. Hendry often works in silence, using photographs she stages herself as references, zooming in to microscopic details most people would never notice. This labor is not hidden. It is embedded in the image, humming beneath the layers of ink.

In Nike Ball, you can feel it—the hours spent darkening a single groove, the meticulous shading that gives the ball its volume. You begin to ask: is this art about a ball? Or about what it takes to draw a ball? Hendry’s works are as much about labor as they are about illusion. She turns the mechanical act of drawing into a meditation on value, time, and surface.

The Ball as Symbol

Why a basketball? And why Nike?

In 2014, when Nike Ball was made, Hendry was still in the early stages of her practice, building a reputation through hyperreal drawings of luxury objects—Hermès bags, Yves Saint Laurent lipsticks, Rolex watches. But Nike Ball marked a turn. It wasn’t luxury in the traditional sense. It wasn’t haute couture or precious metal. It was athletic. Mass-produced. Ubiquitous. And yet, just as fetishized.

Nike, more than any other sports brand, has become a vessel for lifestyle projection. Its Swoosh is shorthand for excellence, drive, power. The basketball, in this context, becomes not just equipment, but myth—of Michael Jordan, of playground heroism, of urban style, of grit turned gold.

Hendry taps into this symbolic field and freezes it. Her drawing doesn’t interpret the ball. It isolates it. Extracts it from action and renders it inert—yet spiritually charged. The ball doesn’t bounce. It hovers. It waits. It watches.

This stillness is crucial. It turns the viewer’s gaze inward. The object becomes a mirror. What does it mean to want a basketball? To draw one for hundreds of hours? To stare at one until it stops being a ball and becomes a question?

Void and Background: The Anti-Environment

One of Hendry’s most powerful visual devices is her use of blank space. The background of Nike Ball is pure white—no context, no texture, no environmental cues. The ball exists in a void. This isn’t laziness. It’s strategy.

By removing any spatial clues, Hendry forces the object into confrontation with the viewer. There is nowhere else to look. No surrounding scene to interpret. The eye must deal with the object as it is, suspended in purgatory. This reduction heightens the surrealism of the realism. The drawing becomes less about the object in space and more about the space within the object.

It also signals a kind of purity—an insistence that the object alone carries enough symbolic weight. Hendry doesn’t need to contextualize the ball in a game or a locker room. Its meaning arrives fully packed.

Drawing as Sculpture

It’s tempting to call Nike Ball a two-dimensional work. But it behaves more like sculpture. Not in the literal sense, but in how it occupies space. Hendry’s use of light and form is so precise that the ball appears to cast a shadow. Its roundness feels touchable. You don’t look at the drawing. You look around it.

This sculptural quality aligns Hendry not with traditional draftspeople, but with minimalists and conceptualists—artists like Donald Judd, who reduced form to experience, or Vija Celmins, whose photo-realist drawings of mundane surfaces evoke infinite depth. Hendry draws the surface of an object but reveals the metaphysical structure beneath it.

A Precursor of Things to Come

Though Nike Ball was completed in 2014, it anticipates many of the directions Hendry would explore in later years: the tension between luxury and banality, the transformation of icons into art, the relationship between visual hunger and material desire.

Her later works would become more colorful, more playful—balloons, inflatables, and large-scale immersive installations. But the DNA remains the same: the elevation of the object through devotion, the commitment to drawing as both discipline and rebellion.

In this sense, Nike Ball is not an outlier. It’s a blueprint. A declaration of intent. It tells us everything we need to know about what Hendry values: precision, patience, contradiction, and the strange emotional gravity of things.

The Art of Looking Too Closely

In a world saturated by images—auto-generated, algorithmically distributed, infinitely replicated—CJ Hendry’s Nike Ball reminds us what it means to really see. To spend hours on a single groove. To mine depth from surface. To make something so real it becomes surreal again.

The drawing may be of a simple ball, a branded sphere, a familiar consumer good. But in Hendry’s hands, it becomes sacred. Not because of what it is—but because of how it is seen, drawn, and offered.

We stare at the ball. And eventually, the ball stares back.

No comments yet.