In an age of software-defined vehicles and algorithmically tuned aerodynamics, it’s easy to forget that the roots of hypercar mythology were not born of electric propulsion or carbon-fiber wind tunnels—but from a moment of impossible ambition in 1980s West Germany. The Porsche 959 wasn’t just a car. It was a rupture in the automotive timeline, a machine so forward-thinking it seemed to have arrived ahead of its time, too complete, too composed, too mythical to exist in the same decade as rotary phones and the Berlin Wall. It didn’t just push boundaries—it redrew them.

Now, four decades later, that legacy is being brought back into full focus through Wundercar, an immersive exhibition curated by London-based creative studio INK. The show, staged in a disused Brutalist warehouse in South London, functions less as a retrospective and more as a sensory case study in obsession. It is a curated fever dream of iconography, archival reconstruction, digital surrealism, and sound—a study in aura. And central to it all is the Porsche 959, recontextualized not as a museum piece, but as a totem of automotive futurism and cultural resonance.

The Machine That Bent Time

To call the Porsche 959 the first hypercar is not hyperbole—it’s acknowledgment. Released in 1986 after years of gestation under the codename Gruppe B, the 959 was originally conceived as Porsche’s response to rally regulations that encouraged advanced technological experimentation. But its ambitions soon outgrew the dirt and gravel tracks of Group B competition. The result was a car so comprehensively engineered that it not only dominated on terrain but redefined the limits of what a road car could be.

A twin-turbocharged flat-six engine pushing 444 horsepower. An electronically controlled all-wheel-drive system—revolutionary at the time. Active suspension. Aerodynamic poly-Kevlar bodywork. Digital dash readouts and tire pressure sensors in an era when cassette decks were still premium options. The 959 wasn’t trying to compete with Ferrari or Lamborghini. It was trying to show the future to people still stuck in the present.

At its launch, the car could hit 60 mph in under four seconds and reach a top speed of 197 mph, making it the fastest production car in the world. But raw numbers miss the point. The 959 wasn’t built to be fastest—it was built to be finest. To synthesize performance, intelligence, and comfort with an elegance that bordered on metaphysical. It didn’t just change Porsche. It changed everything.

INK’s Vision: The 959 as Cultural Artifact

What Wundercar does so masterfully is treat the 959 not merely as a machine, but as a symbol. A work of design that belongs as much in conversation with Memphis Milano as with Le Mans. INK’s approach avoids nostalgia. It doesn’t try to recreate the ‘80s with neon props or synth soundtracks. Instead, it uses minimalism, chiaroscuro lighting, and speculative digital renderings to place the car in suspended animation—eternal, intact, and unplaceable in time.

The 959 on display isn’t static. Projected animations dissect its internals layer by layer. Augmented reality headsets let attendees “drive” the car through dreamlike interpretations of Tokyo, Dubai, and Nevada—landscapes rendered not as photo-real simulations, but as stylized paintings of automotive desire. Overhead, looping sound installations composed by British techno producer Actress draw from engine notes, turbo spooling, and wind tunnel recordings, creating a musical score for a car that always sounded like it came from another dimension.

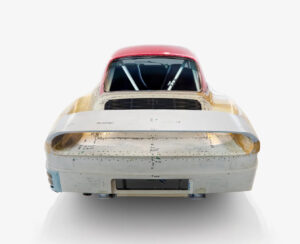

One installation in particular—titled Suspension of Belief—freezes the 959 in midair, suspended by near-invisible carbon-strung wires, rotated slowly by a turntable mechanism. It evokes an object not just rare, but reverent. A relic from the future masquerading as a vintage car. Viewers walk beneath it like visitors to a holy shrine. The message is clear: this was not just a sports car. This was Porsche’s act of prophecy.

Aura, Beyond Utility

Why has the 959 maintained such power in the cultural imagination? It’s not because of how many were made (only 337), or who owned them (Bill Gates famously imported one before it was street-legal in the U.S.). It’s because the 959 captured something ineffable—the kind of machine that felt less like it was assembled, and more like it was summoned.

In his seminal 1935 essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” Walter Benjamin famously questioned whether aura could survive in the era of mass production. The 959 answers with a paradox: it was a production car, yes—but one assembled by hand, governed by software, and priced like a manifesto. It resisted commodification even as it heralded the future of commodified technology. It had the precision of a scalpel, and the soul of a sculpture.

Wundercar leans into this duality. One section of the exhibition displays six archival steering wheels side-by-side—each with minor tooling variances, a subtle reminder that even at this elite level, no two 959s were truly identical. Another room showcases wind tunnel clay models with faint human fingerprints still visible. A documentary loop runs footage of Porsche’s engineers in Weissach nervously adjusting suspension calibrations, staring into oscilloscopes, smoking nervously. The viewer isn’t just witnessing a car—they’re witnessing the psychic labor of future-making.

The Hypercar’s Origin Myth

The term “hypercar” has been retroactively applied to many machines, but few meet the criteria that the 959 quietly established: holistic performance, technological innovation, radical luxury, and a design that aims not to reflect contemporary taste, but to outpace it. Without the 959, there is no McLaren F1. No Bugatti Veyron. No Koenigsegg Jesko. It set the template, even if it didn’t scream about it.

Where Ferrari fixated on lineage and Lamborghini on spectacle, Porsche built something that bordered on anonymity. The 959 didn’t flaunt its brilliance. It embedded it. Unlike the Countach or the Testarossa, the 959 wasn’t poster bait for teenage bedrooms. It was something more adult, more enigmatic. A supercar that wore a tailored suit instead of a leather jacket.

The exhibition explores this thematic restraint beautifully. A three-minute looped film titled Ghostline follows a silhouette of the 959 traced in light as it disappears into fog, morphing between digital wireframe and tangible metal. It doesn’t celebrate horsepower or torque. It celebrates presence.

The Politics of Rarity and the Future of Worship

In the age of NFTs, AI-designed concept cars, and hyper-limited “drops,” the Porsche 959 feels almost utopian. It was rare because it had to be. Because each unit pushed the limits of what was feasible in the analog-to-digital transition of late 20th-century engineering. Today, rarity is often curated artificially. Scarcity is marketing. The 959’s scarcity was mechanical.

Wundercar refuses to reduce the 959 to a flex. It’s not here to help you inflate your portfolio or outbid rivals. It’s here to remind you that some machines were built not to be traded, but to be revered.

And yet, the exhibition is not conservative. It embraces new media. It sees the 959 as a node, not a monument. Its influence echoes into contemporary design—from Rimac’s EV supercomputers to Lucid’s wind-honed sedans. The 959 taught the automotive world that power without precision is noise, and that speed without sense is fleeting. It proved that innovation is best when it’s invisible—when it simply works.

Impression: Toward a New Mythology

If Wundercar succeeds in anything, it’s in reviving the emotional charge of the 959 without letting it fossilize into a nostalgia object. It frames the car not as retro tech, but as living proof that some ideas arrive before the world is ready for them—and wait patiently for their context to catch up.

The Porsche 959 was, is, and remains a wunder. Not just for what it did on the road or in the rally stage, but for how it made people feel: that the future was tangible, that excellence was possible, and that machines—when imbued with care, clarity, and imagination—could transcend their function.

That’s not a lesson limited to cars. That’s a design principle. And one worth sitting with.

No comments yet.