In the early 2000s, Chinese contemporary art was entering a moment of profound self-reflection. Global markets were awakening to its dynamism, and artists of the post-Cultural Revolution generation found themselves tasked with carrying memory across the rupture of history. Zhu Yiyong’s Memory of the Past Series No. 24 (2007), a haunting oil on canvas later consigned to Heritage Auctions, captures this tension with unflinching precision.

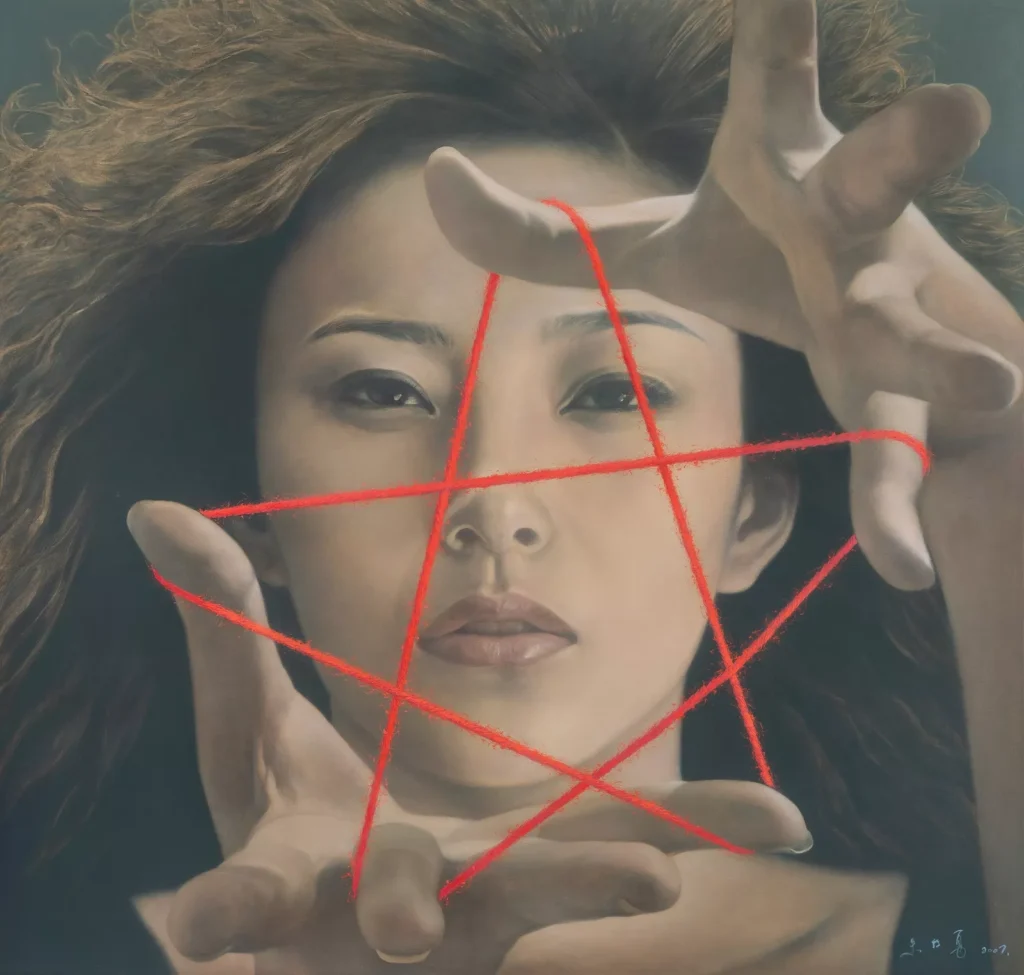

At first glance, the viewer is arrested by the hypnotic gaze of a woman framed by a red pentagram stretched across her hands. Yet the work resists simple categorization: it is not merely a realist portrait, nor is it a straightforward political allegory. Instead, it sits at the intersection of personal recollection, collective trauma, and the mythologies of modern identity.

Zhu Yiyong: An Artist of Quiet Subversion

Born in Chongqing in 1957, Zhu Yiyong grew up in the aftermath of the Great Leap Forward and matured as an artist during the Cultural Revolution. He trained at the Sichuan Academy of Fine Arts, a crucible for the Scar Art movement, which emerged in the late 1970s as artists began to process the psychic scars left by Maoist campaigns.

Zhu, however, carved out a distinct trajectory. Where some peers turned to overt political critique or surreal symbolism, Zhu’s realism was restrained, tinged with melancholy rather than outrage. His Memory of the Past series, launched in the 1990s, exemplified this ethos. These works often feature anonymous figures framed in gestures of silence, concealment, or tension, hinting at suppressed histories that linger within China’s collective consciousness.

By 2007, when No. 24 was painted, Zhu had honed his approach to memory as both intimate and universal—a paradox where individual faces speak to an entire generation’s muted recollections.

The Red Star and the Silent Face

The composition of Memory of the Past Series No. 24 is deceptively simple but laden with meaning. At the center is the hyper-realistic depiction of a woman, her expression at once serene and inscrutable. Her hands extend toward the viewer, fingers splayed, as if both offering and shielding. Across them stretches a glowing red pentagram, drawn like chalk or string, cutting across her face.

Several layers of symbolism immediately unfold:

-

The Color Red: In Chinese political history, red is the color of revolution, sacrifice, and ideology. It evokes the omnipresence of communist propaganda, but also the cultural connotations of luck, vitality, and festivity. Zhu reappropriates red here not as celebratory, but as binding—its chalky texture resembling both graffiti and blood.

-

The Pentagram Form: The five-pointed star is inseparable from the iconography of the People’s Republic of China, appearing prominently on the national flag. Yet when stretched across a face, it ceases to be a mere emblem of nationhood and becomes instead a cage, a mark of possession.

-

The Gaze: The woman’s eyes are steady, unflinching. Unlike propaganda posters of smiling peasants or heroic workers, her expression is stripped of performativity. She looks not at the collective future but into the private present, challenging the viewer to reckon with what the star conceals.

-

Gesture as Language: Her hands, which seem to draw or hold the star, suggest agency. She is not merely marked but complicit in arranging the lines, as though the past is both imposed upon her and enacted by her own motions.

The combination of realism with symbolic intervention produces a disquieting effect: memory becomes material, etched across the body, forcing confrontation rather than erasure.

Memory and Post-Mao China

The title of the series—Memory of the Past—demands contextualization. In post-Mao China, memory was a fraught terrain. The state encouraged selective remembrance: celebrating revolutionary triumphs while suppressing recollections of famine, purges, and personal suffering.

For artists like Zhu Yiyong, memory became a counter-archive. By placing ordinary figures under symbolic duress, Zhu re-inscribed the silences of history into the visible realm. No. 24 belongs to a period when Chinese society was undergoing rapid globalization and economic transformation, yet historical reckoning remained elusive.

The star across the woman’s face thus speaks to both the persistence of ideology and its fading relevance. It is at once a scar from the past and a reminder that history cannot be disavowed simply by economic progress.

View this post on Instagram

Realism as Strategy

Zhu’s style is hyper-realist, yet it diverges from Western photorealism. In China, realism carried a distinct lineage, tied to socialist realism of the Maoist era. That style was once a state-mandated instrument of propaganda, idealizing workers, soldiers, and peasants.

By the 1990s and 2000s, Chinese realist painters reappropriated the technique, stripping it of utopian gloss. Zhu’s painstaking detail recalls propaganda posters but subverts their ideological clarity. Where the state once deployed realism to erase ambiguity, Zhu reintroduces it. The woman’s face in No. 24 is not heroic, not idealized, but human, complex, and unresolved.

In this sense, realism becomes Zhu’s weapon of critique: he uses the very tools of propaganda to undo its authority.

The Female Subject and Symbolic Burden

It is no accident that Zhu centers a woman in No. 24. Female figures recur throughout his series, often depicted with hands raised, mouths covered, or faces obscured. Women, in Zhu’s visual lexicon, function as bearers of memory precisely because they are marginalized in official narratives.

By overlaying the star upon her, Zhu emphasizes the intersection of gender and ideology: how women’s identities were often subsumed by collective revolutionary rhetoric, their individuality silenced in favor of archetypes (the worker, the mother, the comrade). In No. 24, however, the woman resists subsumption. Her gaze pierces through the red lines, asserting presence despite erasure.

From Private Memory to Global Market

When Memory of the Past Series No. 24 appeared as Lot 21001 at Heritage Auctions, it marked not just the circulation of a single artwork but the globalization of Chinese memory. Auction houses in the 2000s became central sites for mediating Chinese contemporary art to international audiences, with figures like Zhang Xiaogang, Yue Minjun, and Fang Lijun fetching record prices.

Zhu Yiyong, while less flamboyant than the “Cynical Realists” or “Political Pop” artists, appealed to collectors drawn to a subtler, more melancholic vision. His works offered both aesthetic refinement and cultural gravitas, engaging Western audiences interested in China’s complex negotiation with modernity.

The sale of No. 24 thus crystallized how memory itself could become commodified—traded in global markets as both cultural testimony and aesthetic object.

Zhu Among His Peers

To fully appreciate Zhu’s distinctiveness, it is useful to compare him with contemporaries.

-

Zhang Xiaogang’s Bloodline: Big Family series depicted anonymous families linked by red lines, symbolizing kinship and ideology. Where Zhang used surreal distortion, Zhu opted for realist intimacy.

-

Yue Minjun’s laughing figures critiqued collective amnesia through grotesque repetition. Zhu, by contrast, resisted irony, preferring sober confrontation.

-

Fang Lijun’s bald figures embodied disillusionment, yet often in public, monumental scale. Zhu localized memory in the private, singular face, resisting spectacle.

Through these distinctions, Zhu’s Memory of the Past series emerges as a quieter but equally powerful contribution to the conversation on post-Mao subjectivity.

Global Readings: Beyond China

While deeply rooted in Chinese historical consciousness, No. 24 resonates globally. The red star, after all, is not only a Chinese symbol but also a universal signifier of socialism, revolution, and ideological utopias. Viewers from Eastern Europe or Latin America may recognize in it echoes of their own fraught histories with communism.

Moreover, the theme of memory under duress—of private identity marked by collective past—transcends borders. In this sense, Zhu’s painting participates in a broader conversation about how nations reconcile with traumatic histories in the wake of modernity.

Critical

Critics have lauded Zhu’s Memory of the Past series for its “subversive stillness.” Unlike overtly satirical artists who dominated headlines in the West, Zhu’s work required patient engagement. The subtlety of his symbolism—hands, stars, lines, silence—invited viewers to linger, to decode, to feel unease.

Art historians have positioned him within the lineage of “new realism,” yet his works resist neat classification. They are neither cynical nor celebratory, neither nostalgic nor futurist. Instead, they dwell in the tension of memory’s persistence, its inability to be erased.

As the global art world increasingly values nuance over spectacle, Zhu’s legacy continues to grow. No. 24 stands as testament to his refusal of easy answers.

Memory as Red Thread

In Memory of the Past Series No. 24, Zhu Yiyong gives form to the paradox of memory in contemporary China: it is both suppressed and inescapable, both personal and collective, both wound and thread.

The woman’s face, bisected by the red star, embodies the way history inscribes itself upon individuals. Yet her steady gaze refuses erasure. Through realism sharpened into critique, Zhu makes visible what official narratives seek to forget.

That this painting now circulates in global auction houses underscores the universality of its themes. In its silence, its restraint, and its haunting ambiguity, No. 24 reminds us that memory is never past—it is always present, always inscribed, always demanding recognition.

No comments yet.